Like electricity: Todd Fuller and 'Billy’s Swan'

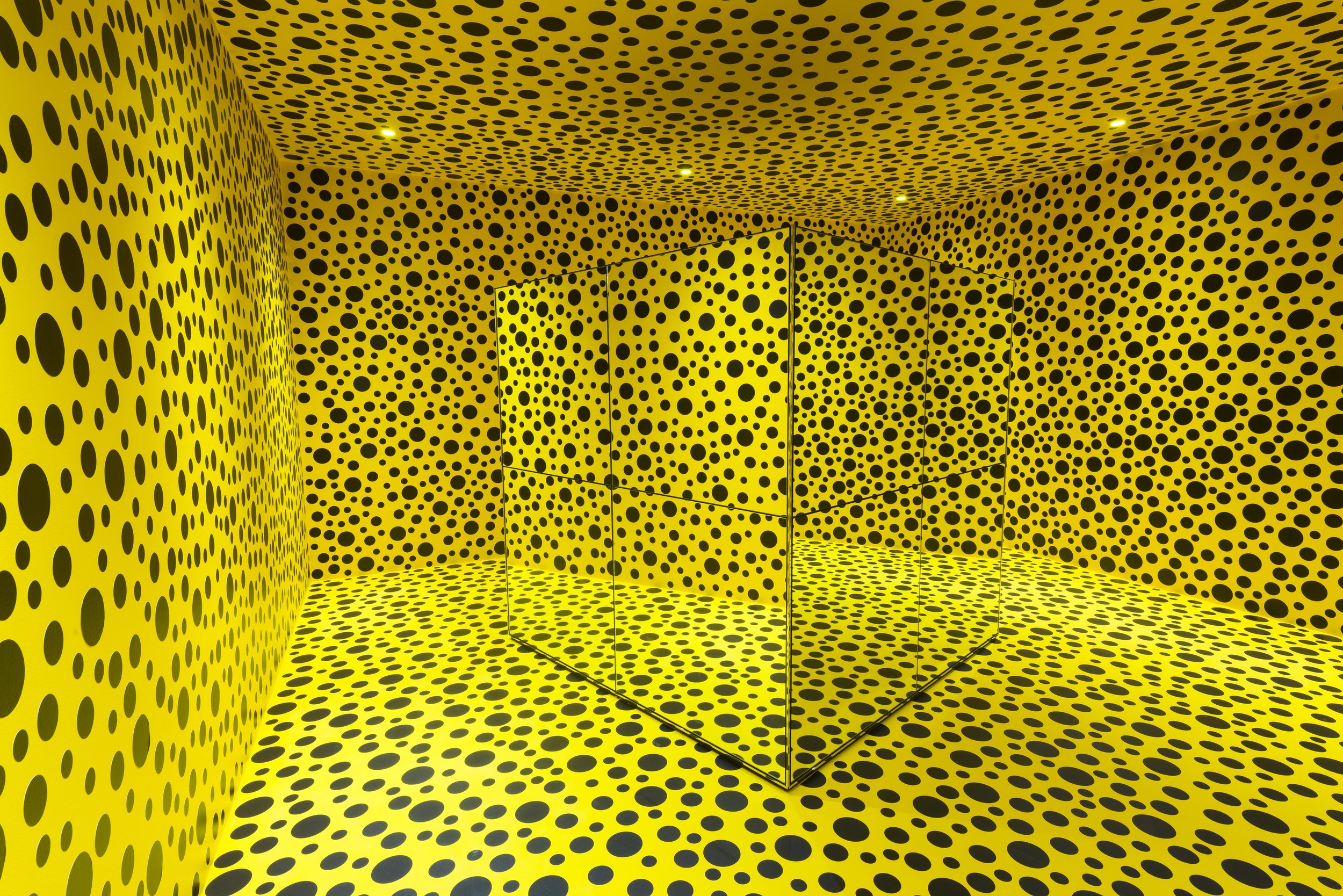

/Todd Fuller, Billy’s Swan, 2017, video still; chalk and charcoal animation and video, 5:37 mins duration; image courtesy the artist and May Space, Sydney

When I think about trauma, my thoughts inevitably drift towards musicals. The emotional, physical, spiritual and sexual abuses I’ve experienced – especially in my youth – somehow shaped who I am today as a queer man who sees the world through music. The genre of the musical thrives from making sunshine of shit. Bad things happen, but transforming them into song and dance makes us feel like everything will be alright in the end.

The film Billy Elliot (2000) was destined for an afterlife as a musical. A young white boy going through the identity crisis of puberty trades his boxing gloves for ballet slippers amid a familial and community backdrop of grief and impoverishment. But when he dances, he transcends his physical or psychic constraints. In a poignant scene where Billy auditions for the Royal Ballet School, he is asked what he ‘feels’ when he dances, to which he responds: ‘… like a bird, like electricity.’

The queerness of Billy Elliot finds fuller form in the musical than the film. With music by Elton John and choreography by Peter Darling, Billy Elliot the Musical made its stage debut in 2005 on the West End in London. Australian visual artist Todd Fuller saw the musical in Sydney in 2007 at the age of 19. A decade later, amid debates about marriage equality in Australia, Fuller’s animation video Billy’s Swan (2017) revisits the musical to weave a personal narrative within the political framework of human rights for LGBTIQA individuals.

In Billy’s Swan (first show as part of the exhibition ‘Out of Line’ at Sydney’s May Space in November last year), Fuller performs to camera an appropriation of Darling’s choreography from the musical. It is rare for Fuller to appear in his videos as a live performer given the focus is generally on whimsical narratives that unfold through drawn animation. Fuller’s appearance bookends the work with chalk and charcoal animation ‘performing’ the bulk of the dance. For Fuller, the live action grounds the work in a sense of reality, with the animation ostensibly offering a space of imagination, fantasy, or ‘electricity’, to quote young Billy.

Similarly, young Todd is being quoted by ‘old’ Todd in Billy’s Swan. On the cusp of turning 30 at the time of its making, Fuller reflects on his teenage life in Branxton, in the Hunter Region of New South Wales where he grew up. From 14 until 17, Fuller studied dance in secret and ‘it was not particularly pretty when this became schoolyard knowledge,’ he recalls. Dance films consumed as a teenager became the locus of his desire to escape the torments of closeted queer youth, much like Darling’s choreography represents Billy’s small-town aspiration to leave home for the glitz of the big city.

As Fuller’s body gives way to charcoal and chalk on screen, the animation evolves through a process of trace and erasure. The drawings come to life through a repeated process of being rubbed out and rearticulated, with the trace of the erased image lingering like a ghost. Derived from ‘dead’ wood, charcoal is a potent material for mark making and unmaking. Made prior to the outcome of the Australian Government’s imposed postal plebiscite about marriage equality, Billy’s Swan reflects on what it could have meant if the LGBTIQA community was ‘rubbed out’ with a majority NO vote. Given that wasn’t the case, it does not even bear thinking about. And yet, in offering dance as a space where queer futures are powered by the electricity of our own making and re-making, Todd Fuller shows us how a position of vulnerability can combat a heteronormative culture fooled into thinking we are weak and without limitless strength.

http://mayspace.com.au/enlarge_works.php?workID=41701&artistID=208

Daniel Mudie Cunningham, Sydney