Turning inwards, and outwards: Galleries in the time of coronavirus

/With galleries and museums around Australia forced to close their doors to ensure the health of staff, volunteers and visitors, opportunities to enjoy and support the arts seem to have been dramatically reduced, almost overnight. The appreciation of art might be the last thing on many minds right now but, as United Kingdom-based arts educator Louis Netter observed in a recent piece for The Conversation, our mutual confinement compels us to turn ‘inward, to the vast inner space of our thoughts and imagination’, a space in which artists have for centuries served as our most faithful navigators. A recognition of this need has prompted artists, curators and gallery owners across the country to explore new platforms for their insights into our shared human condition, demonstrating clearly that, although the doors of our homes and businesses may be closed, those of our imagination remain defiantly open.

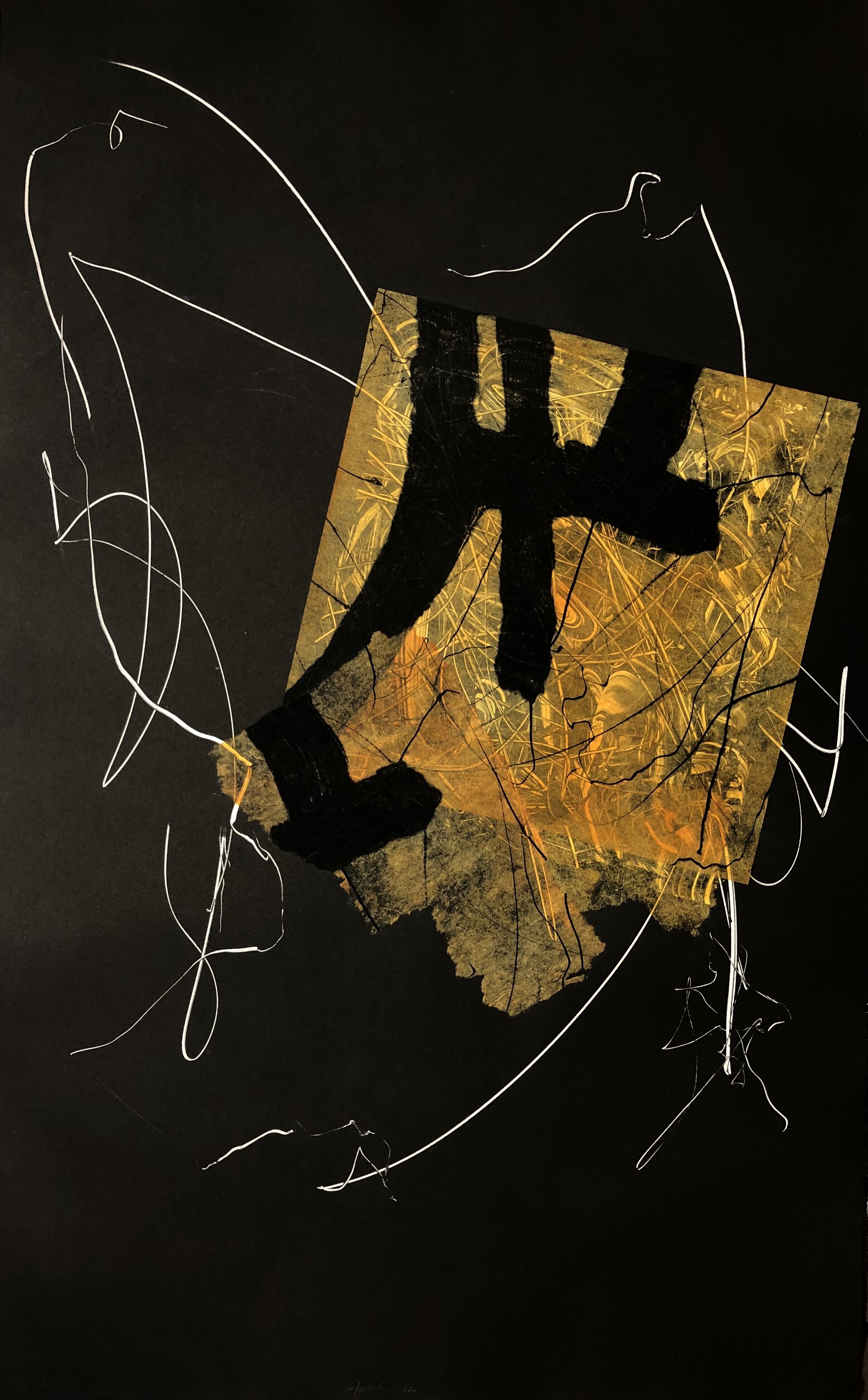

At Raft Artspace in Alice Springs, a selection of works from Mimili Maku Arts celebrating family, home and community can be viewed on the gallery’s website or enjoyed in situ in a video tour shared to their Instagram. From the ruddy tones of Judy Martin’s Ngayuku Mamaku Ngura (My Father’s Country) to the vivid, pulsating polychrome palette of Linda Puna’s Ngayuku Ngura (My Home), these paintings offer a reassuring reminder of the support and creative inspiration that this arts centre in the Everard Ranges provides, even in times of global crisis. Solander Gallery in Wellington have made works by New Zealand-based artist Jacqueline Aust available to browse and purchase online. Aust’s fascination with the experience of displacement and her respectful engagement with the aesthetics of calligraphy, inspired by a recent trip to Japan that coincided with a devastating typhoon, reinforce the pressing need to empathise with the suffering of others as prejudice and paranoia infect the world.

A new series of photographic works by Lisa Reihana, another renowned New Zealand artist, are available to view and purchase on the website of the newly opened Gallery Sally Dan-Cuthbert in Sydney. Drawn from her immersive three-dimensional film Nomads of the Sea, Reihana’s empowering images weave together history and fiction in a manner that followers of her work will recognise as an extension of ideas explored in her first major video in Pursuit of Venus [infected], available to watch on the artist’s website. Nomads of the Sea is also featured in this year’s Sydney Biennale, currently developing a range of ‘digital activations and experiences’.

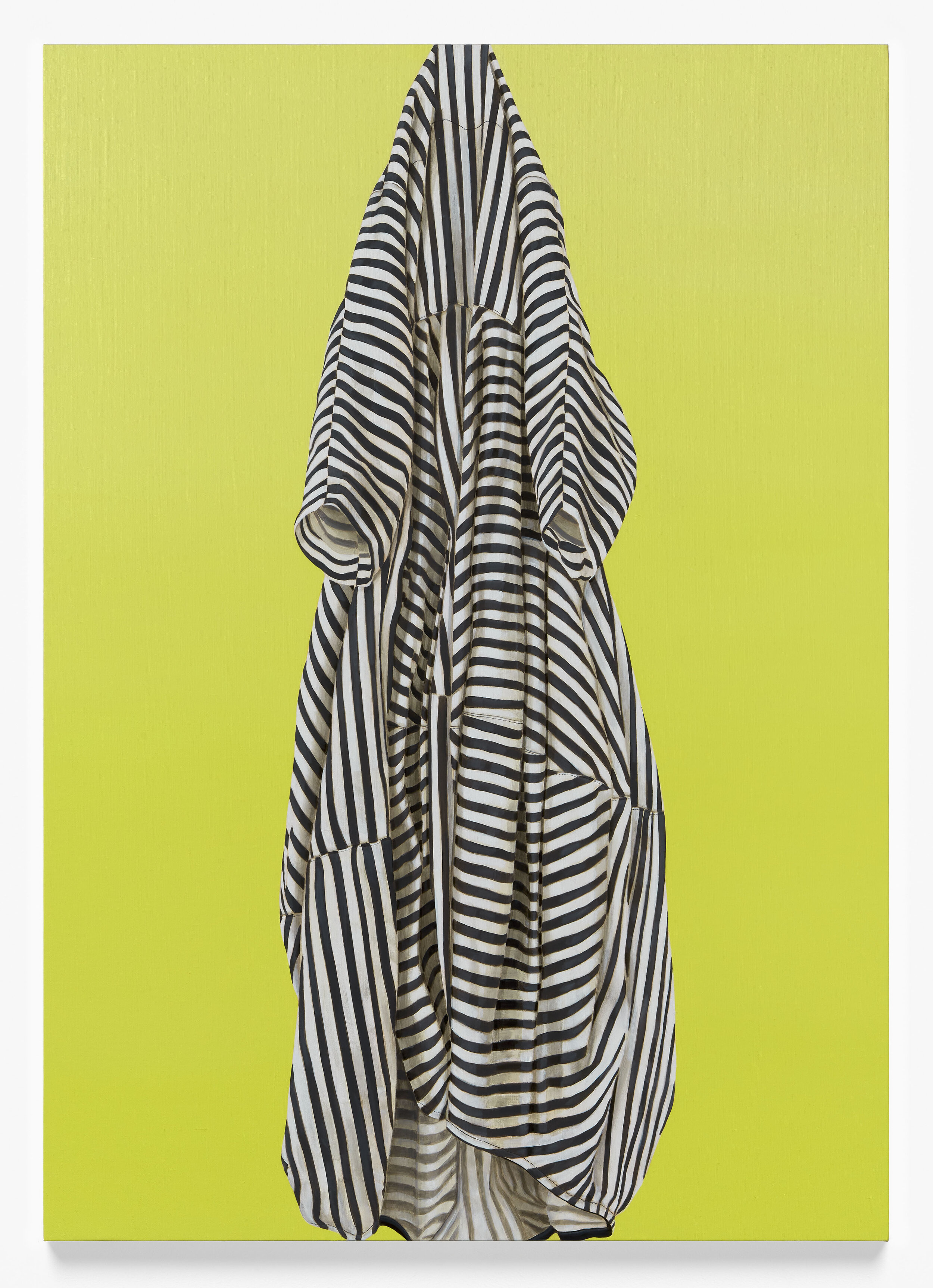

Fans of Melbourne-based artist Jan Murray’s technicolour portraits of stylish jackets, shirts and dresses, their ‘optically dazzling designs of black-and-white polka dots, green and pink chevron weaves, and red and white zigzagged stripes … set against eye-popping backgrounds in citrus and neon tones’, in the words of AMA regular Chloé Wolifson, can browse her paintings in all their glory on the Charles Nodrum Gallery’s website. Those who’d like to learn more about Murray’s work will enjoy an extended essay by art historian Helen McDonald, also available online.

The AMA team is working to expand online accessibility in response to our current global circumstances – digital subscriptions (including access to an archive of back issues from March 2008 to March 2020) are available as always for purchase on our website, and we’ll continue to bring you our coverage of the latest events and exhibitions on this blog, proudly open access. Keep an eye on our new Twitter profile and our Facebook page for more updates!

Dr Alex Burchmore, Publication Manager