Through lines: ‘2021 Adelaide//International’ at Samstag Museum of Art

/

The iterative exhibition series presented by Adelaide’s Samstag Museum of Art – centred on the curatorial premise of past, present and future – was, in its third and final instalment this year, poised to deal with the difficult (and current) challenge of looking ahead. Curator Gillian Brown prudently shifted things away from projection towards process. Across four bodies of work a fractal pattern of exhibition-making emerged – an exhibition inside an exhibition inside an exhibition – with subjects and through lines that proved timely yet timeless.

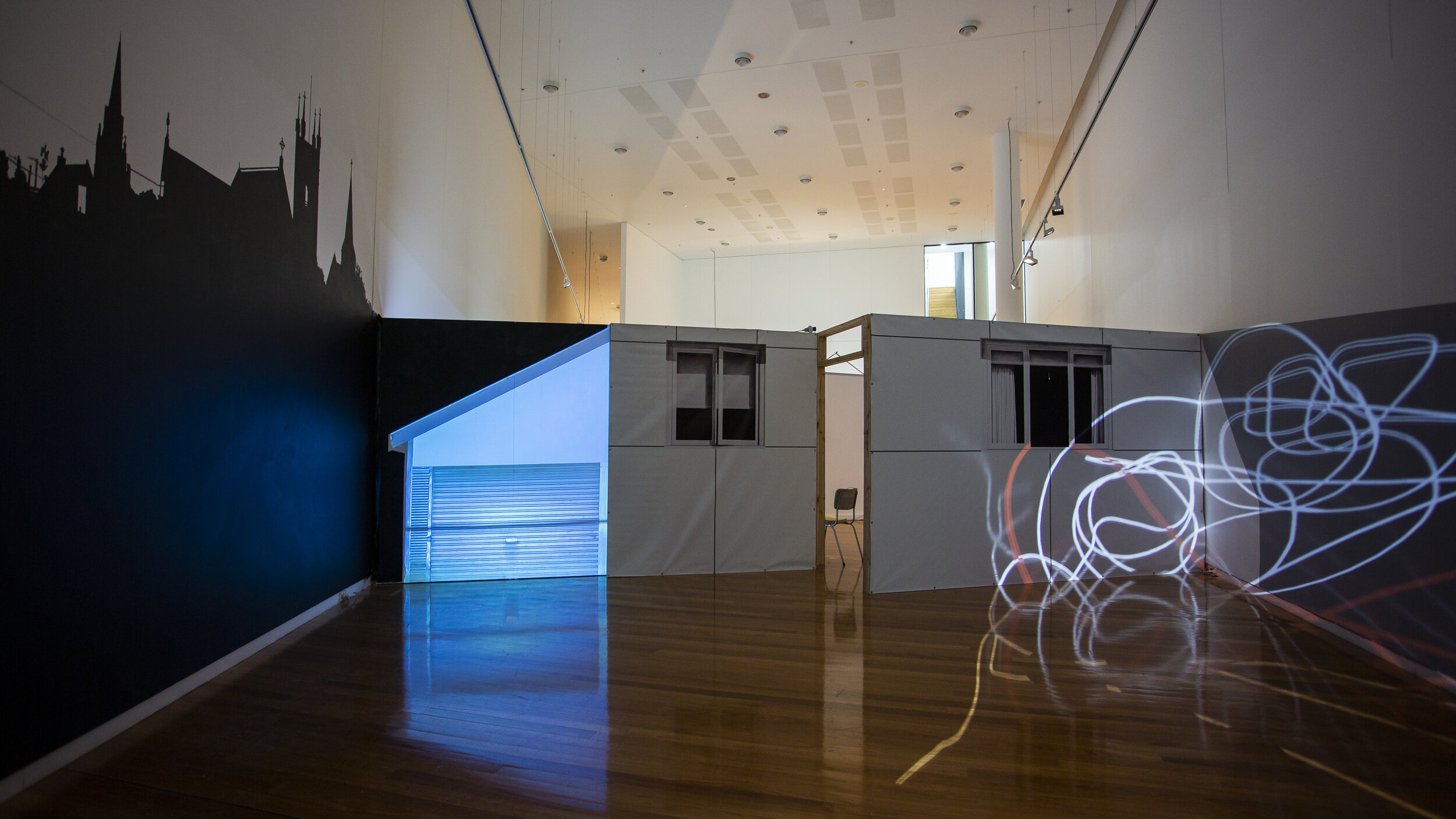

In Irish artist Jesse Jones’s Tremble Tremble (2017), a central figure apparated in the room, a white-haired Celtic giantess summoning the words of women who were murdered for practising witchcraft. At the time of viewing, Adelaide artist Eleanor Amor was charged with evoking the talismans of Jones’s expanded cinematic installation: an etched portal on the wall; a ring of hewn wooden tools; the scaled-down relics of courthouse architecture wrapped umbilically in beeswax.

Although Tremble Tremble was conceived against Jones’s own political backdrop – in 2018, Ireland repealed the eighth amendment in an historic referendum allowing for abortion – it is equally resonant on Australian shores. As #March4Justice took over Australia’s public and virtual domains, triggered by allegations of rape and women’s (lack of) place in the halls of power, Tremble Tremble reminds us that the history of witchcraft is also the history of women and the law.

Systems of law are taken up in Taloi Havini’s Tsomi wan-bel (2017), a three-channel video depicting a living practice of restorative justice in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville. From the opening shots looking out from the island’s edge and the tight, direct gaze of the film’s three subjects – the perpetrator, the mediator and the victim – Tsomi wan-bel unfolds as a culturally coded model of reconciliation, its hybridised title meaning win-win.

The significant act of Tsomi wan-bel is its omission. Havini’s directorial eye leads us to the peripheries of the village court rather than the dispute itself. In focusing on the objects and practices of kastom – preparation of pig, taro and sweet potato; chewing betel nut; reactions of community members on the sidelines – she carefully avoids the (often uninvited) scopophilic lens of the documentarian. Instead, Havini symbolically captures the people, place and processes of an embodied judiciary system.

The presence of absence is also palpable in James Tylor’s The Darkness of Enlightenment (2021). In Tylor’s case, absence is physically scored into the 18 photographs and 31 blacked-out carvings that make up the installation – an archive of memorialisation. Tylor works hard to scrutinise Adelaide’s founding premise of ‘settlement’ in his depiction of Kaurna cultural sites (material and geographic) marked by this untruth. Of course, where there is void there is space. And, The Darkness of Enlightenment artfully occupies; Tylor rewrites redacted histories through living language and cultural continuity.

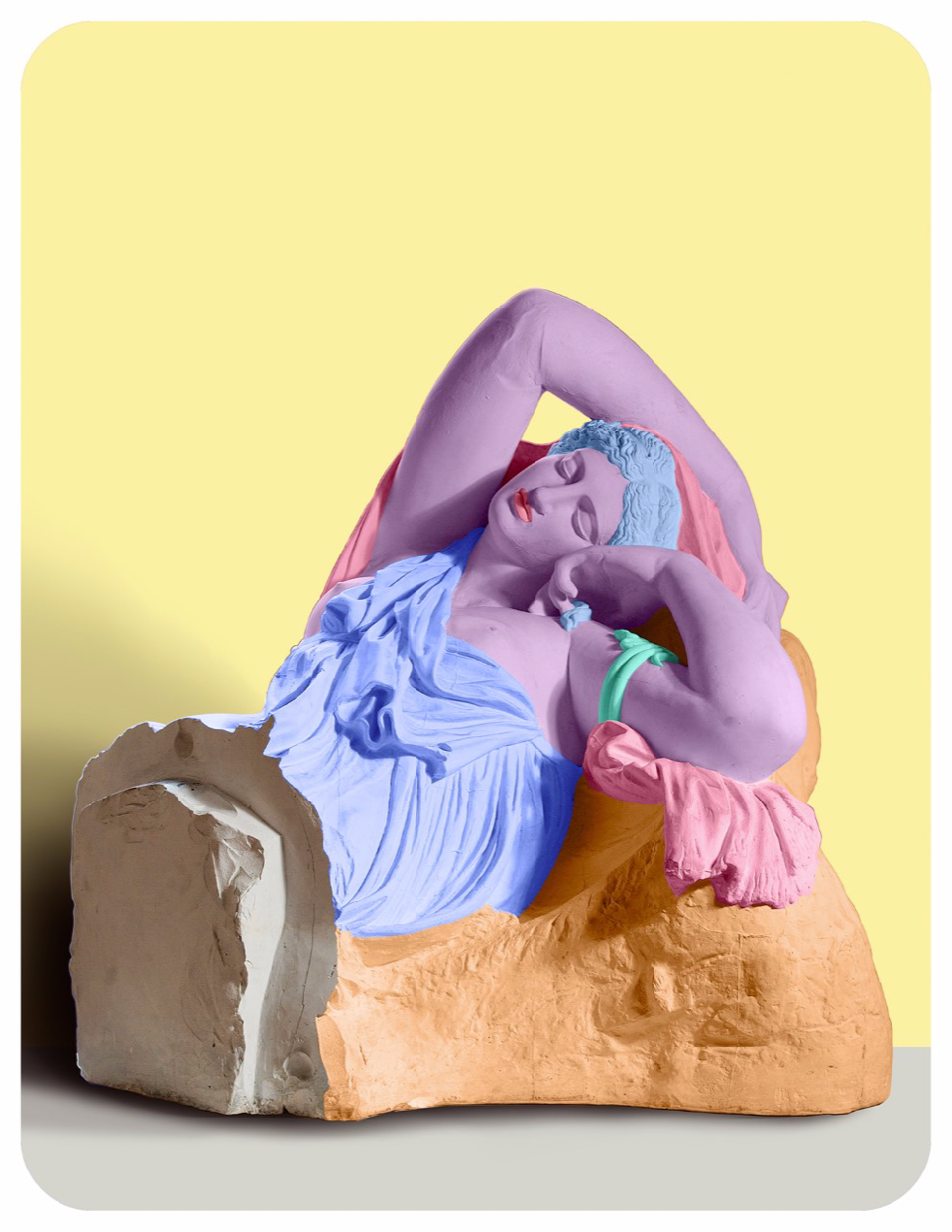

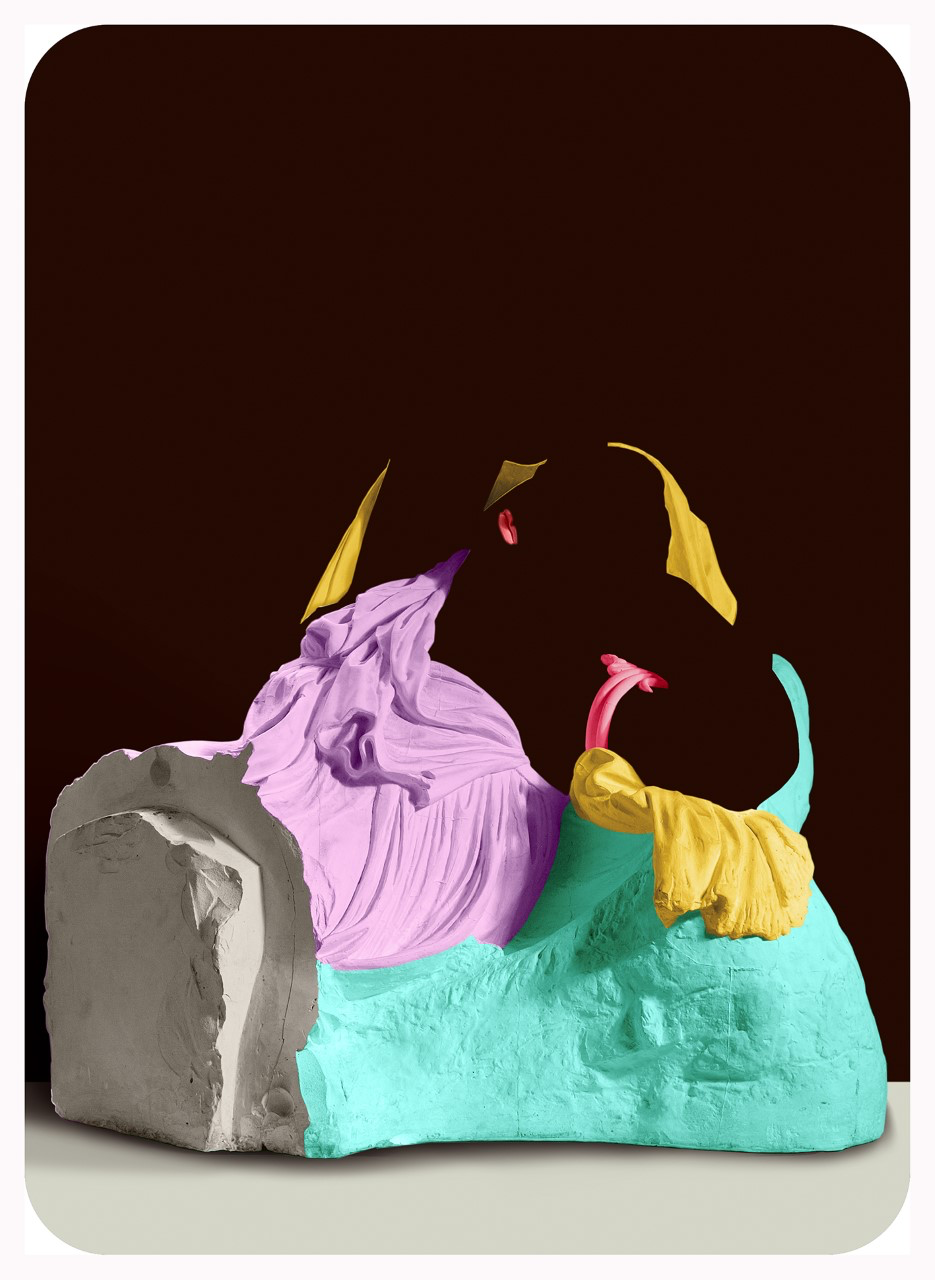

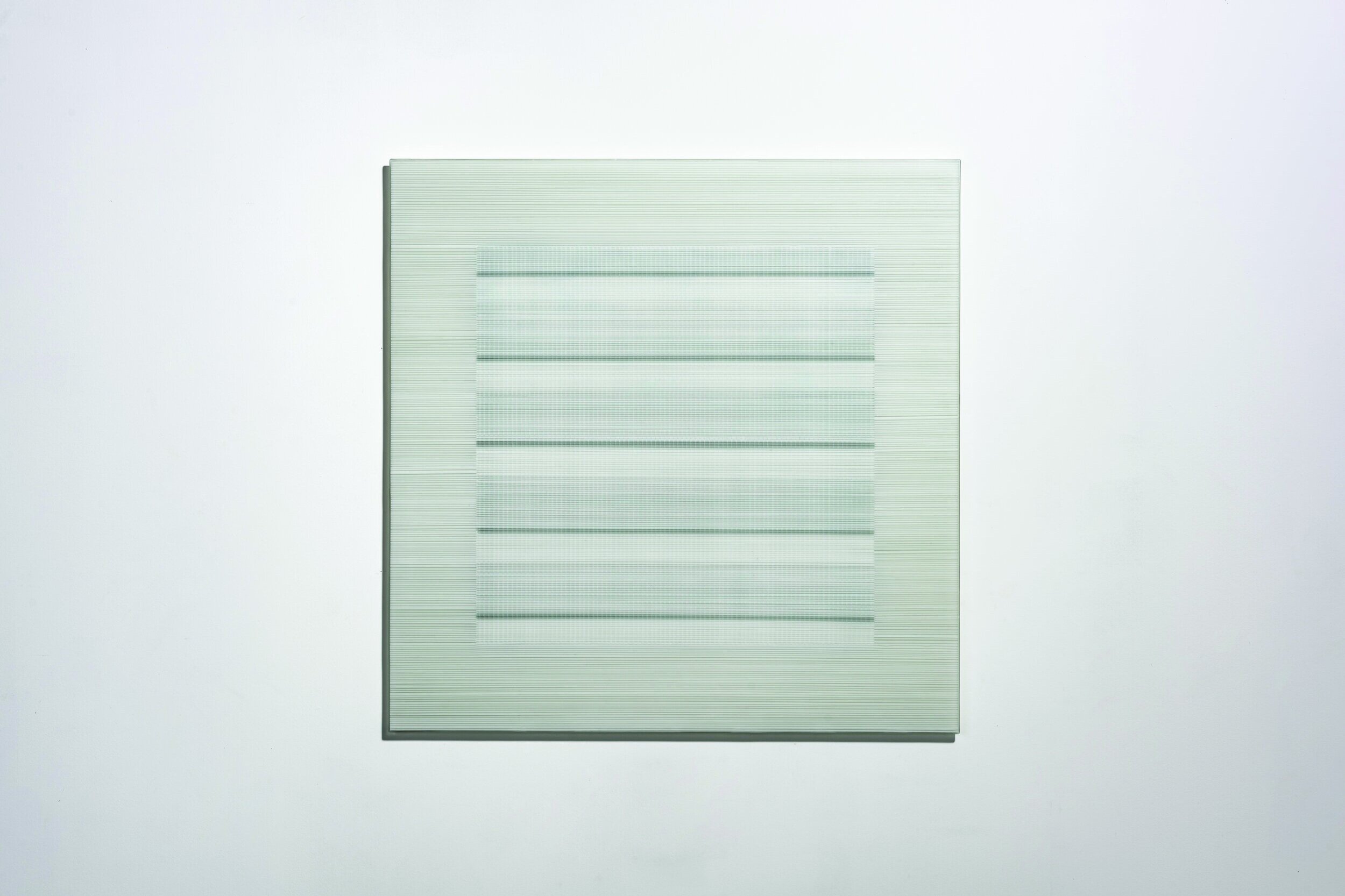

In the final turn of ‘2021 Adelaide//International’, Fayen d’Evie’s Endnote: The Ethical Handling of Empty Spaces (2021) left us with a proposition: how might we transmit our stories into the future? D’Evie’s reply is found in the material properties of language. Drawing on her experience of blindness, her speculative texts are driven by tacit, embodied knowledge – ‘essays’ scribed in marble, stone and wood, signs transcribed into printed typography. As dancer and choreographer Benjamin Hancock performed between D’Evie’s suppositional works, he iterated a single phrase through motion – an arm held, a body poised, a gesture echoing into the future.

Belinda Howden, Adelaide

Curated by Gillian Brown, ‘2021 Adelaide//International’ was on display at Samstag Museum of Art, University of South Australia, from 26 February until 1 April 2021.