Satiating artists and audiences: ‘SIMMER’ at MAMA

/The verb simmer describes a liquid substance bubbling gently, just below boiling point. The Oxford English Dictionary also defines simmer as ‘to be in a state of subdued or suppressed activity’. Collectively, we simmered away during last year’s COVID-19 lockdowns: trapped inside, cut off from family and friends, worlds reduced to the interior of our respective homes. When we were finally freed, joy bubbled to the surface. We gathered around picnic rugs, sharing food and drink in a burst of frenzied activity. ‘SIMMER’ at Murray Art Museum Albury (MAMA) embodies these sentiments. According to its website, the exhibition aspires to consider ‘how food can bring us together, break down barriers and open us up to new experiences’. This is a well-rehearsed line of enquiry in studies of food-related artwork. French curator Nicolas Bourriaud applied the term ‘relational aesthetics’ to describe practices emergent in the 1990s that reintegrated social contact into art encounters. Bourriaud theorised that such work could repair social bonds weakened through feelings of alienation or isolation. Following a period of fractured social relations from the enforced separation caused by the pandemic, ‘SIMMER’ similarly addresses the ways food can engender kinship and bonding.

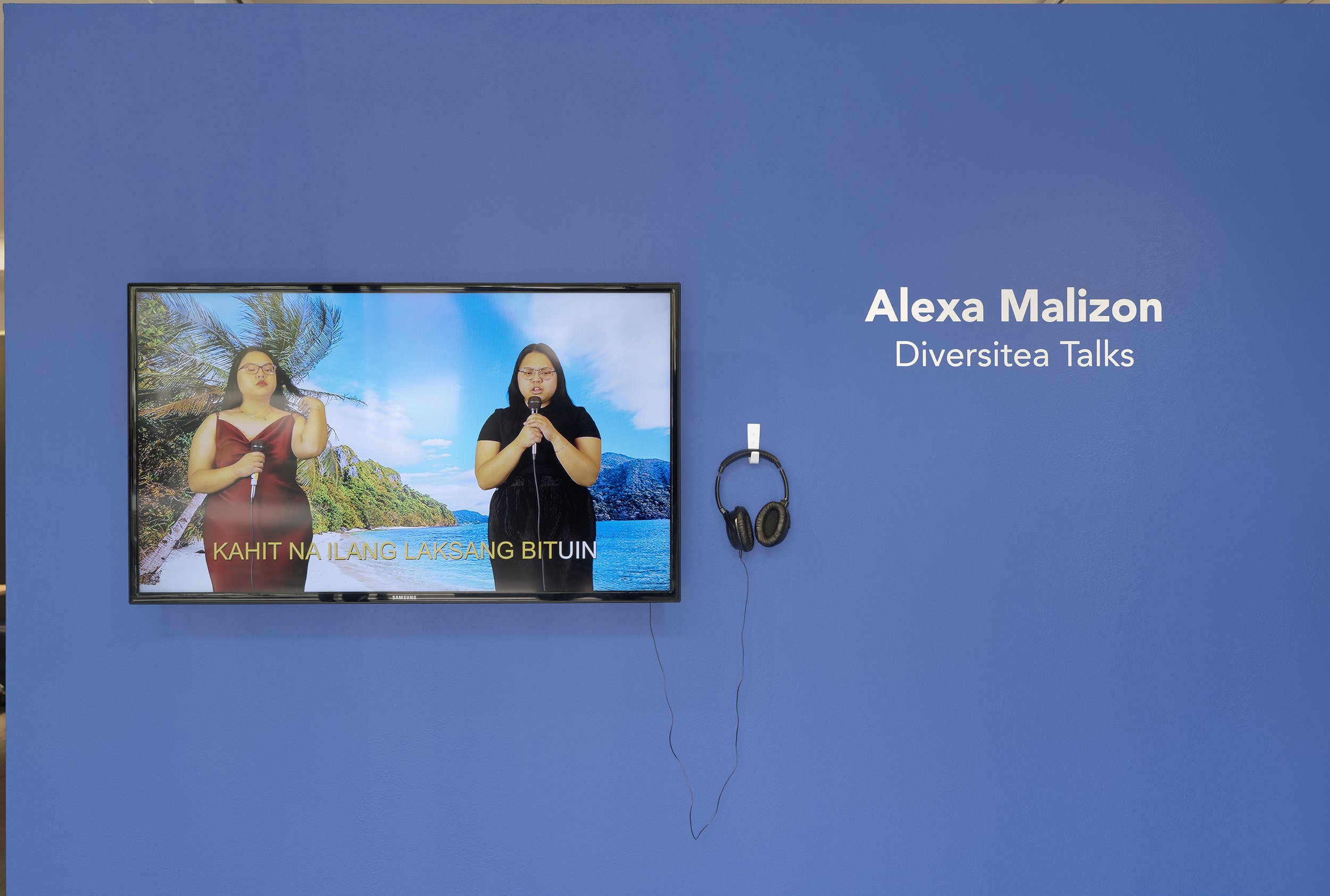

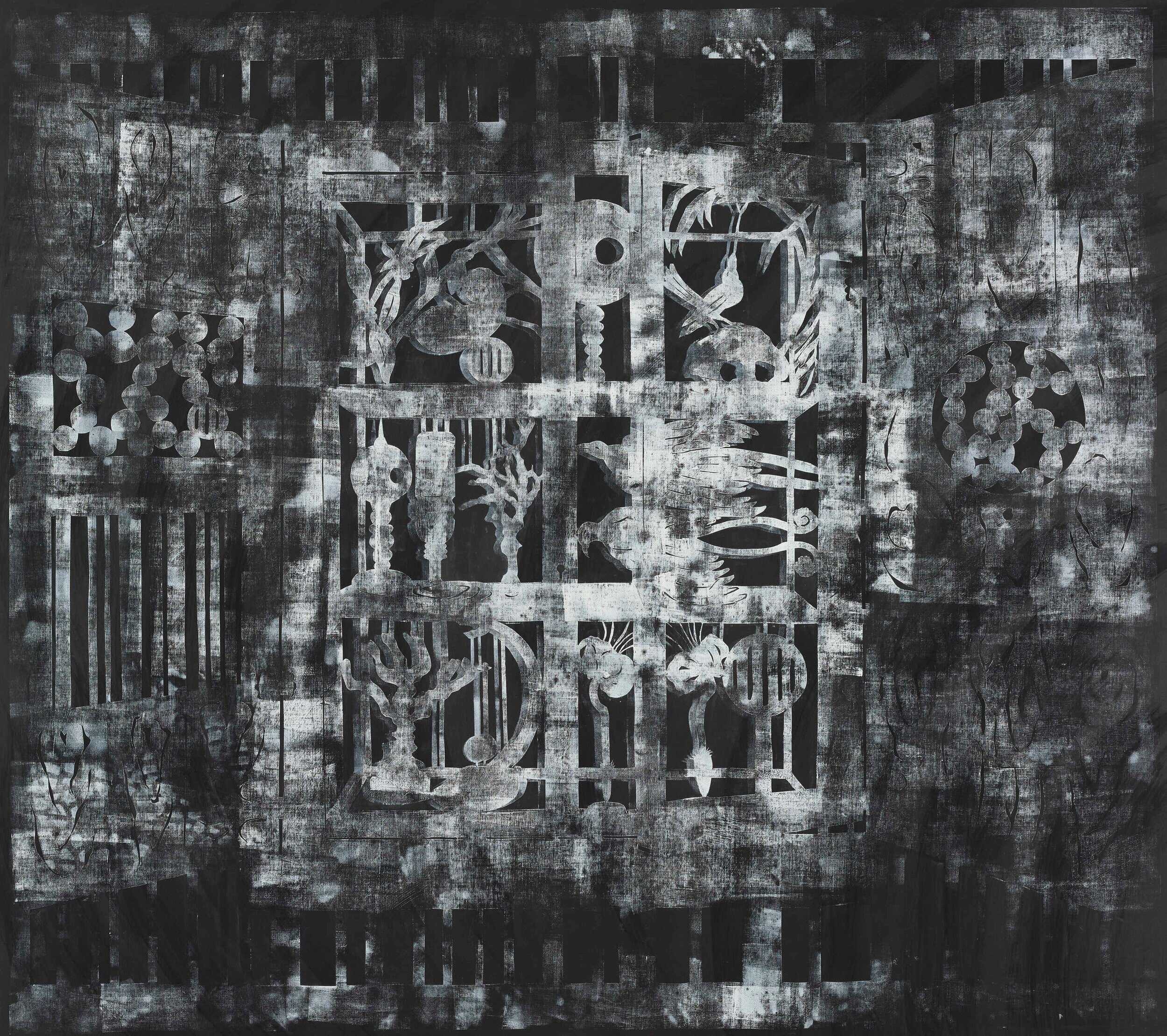

Many of the artworks selected by curator Nanette Orly explore the cultural significance and social relations implicit in preparing and sharing foodstuffs. Singaporean-Australian artist Nabilah Nordin’s installation Domestic Dough Facility (2021) involves sculpted dough mixers and conveyor belts devoid of their functionality alongside an assortment of oddly shaped, rock-hard bread. The latter is a highly symbolic foodstuff; we say to ‘break bread’ to describe kinship practices involving food. American artist Eva Aguila’s Comida a Mano (2019) frames tortillas as a tangible link to her Mexican heritage, and British artist Navi Kaur’s Mērā Ghar (2021) involves deeply personal familial rituals linked to food, culture and faith. Both films consider how food production and consumption can serve as a method to maintain social and cultural ties, especially for individuals who resettle in a new country.

Australian artist E. J. Son’s T tree (2021), an assemblage of fleshy nipples, abstracts the forms of capsicums and tomatoes to appear like the soft petals of a flower. Son casts the produce’s rounded ends in flesh-toned silicone and inserts a replica of a human nipple in the middle. Son’s titillating tree entwines the ripened reproductive organs of flowers (or fruits) with a part of the female anatomy that is both sexualised and a source of nourishment for infants. The work speaks to our earliest experience combining eating and social interaction – breastfeeding – an act of care that forms social bonds between child and mother.

‘SIMMER’ offers audiences a global survey of food-based customs and presents a veritable feast to a travel-starved population. It relates to a seemingly similar show at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, ‘The Way We Eat’, a display drawn mainly from the museum’s Asian art collection that explores food consumption by way of vessels, tableware and banquet scenes. As we start to reconnect with our family and friends, MAMA’s exhibition reminds us of the role foodstuffs play across cultures in cementing social bonds and in bringing into sensorial focus the essential relationship between artist and audience.

Megan R. Fizell, Albury

Curated by Nanette Orly, ‘SIMMER’ is on display at the Murray Art Museum Albury until 13 February 2022.