Tell me you’ll come: ‘THE PARTY’ at UNSW Galleries

/Queer nightlife in Sydney stands at a critical juncture. The relaxing of lockout laws have temporally coalesced with a COVID-era appreciation for leisure and togetherness. We’ve had more than enough time with certain apps and the city seems once again desirous of bodies-meeting-in-space. This moment presents itself with an opportunity, then, to revere our wonderful history, to take stock of all that has come before. To energise and organise for the city we deserve.

‘THE PARTY’ arrives like Bianca Jagger on a white horse. A collaborative exhibition between José Da Silva, Director of UNSW Galleries and Curator of the 2024 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art, and Nick Henderson, Curator and Volunteer Collection Manager of the Australian Queer Archives, ‘THE PARTY’ explores Sydney’s queer party ecologies between 1973 and 2002, presenting a dizzying array of handmade ephemera including posters, flyers, tickets, photographs, videos, wearables and more.

The objects on display skilfully shift the focus away from luminary designers like Ron Muncaster and Peter Tully, giving space for a great many others to be honoured and remembered. Crucially, the exhibition brings attention to the revellers themselves and evidences the intensely collaborative and grassroots spirit of those decades.

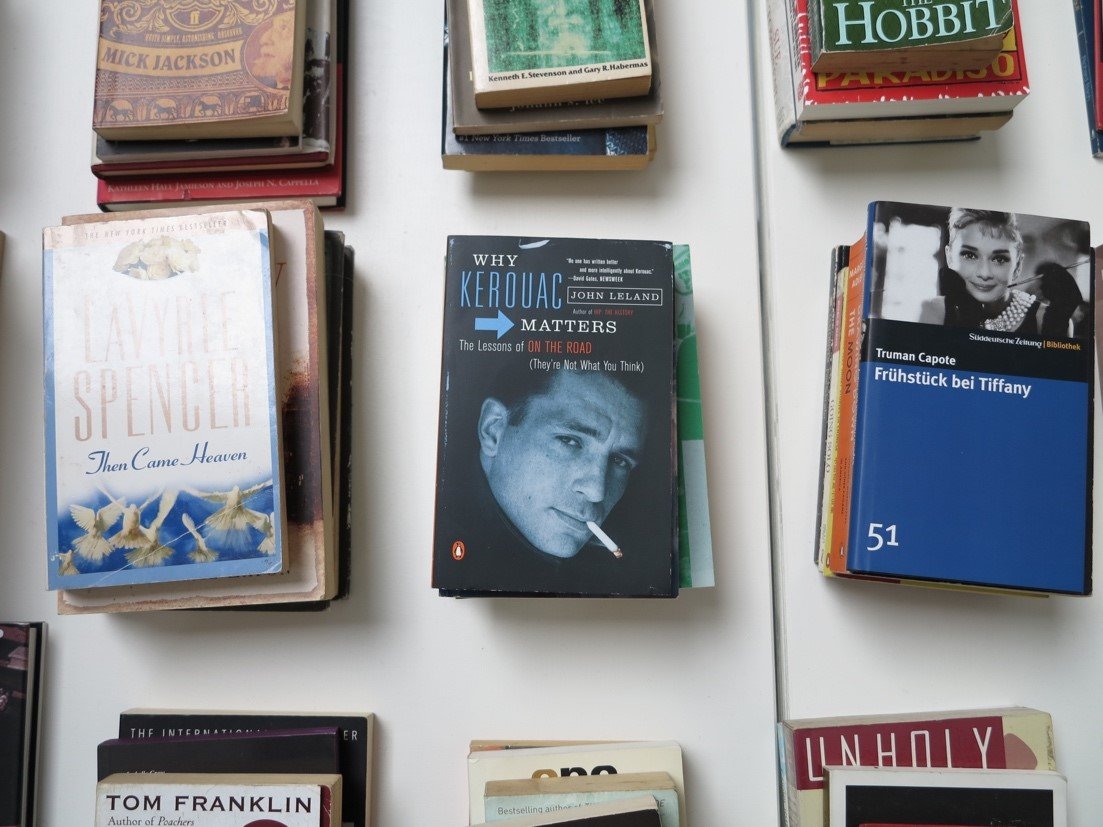

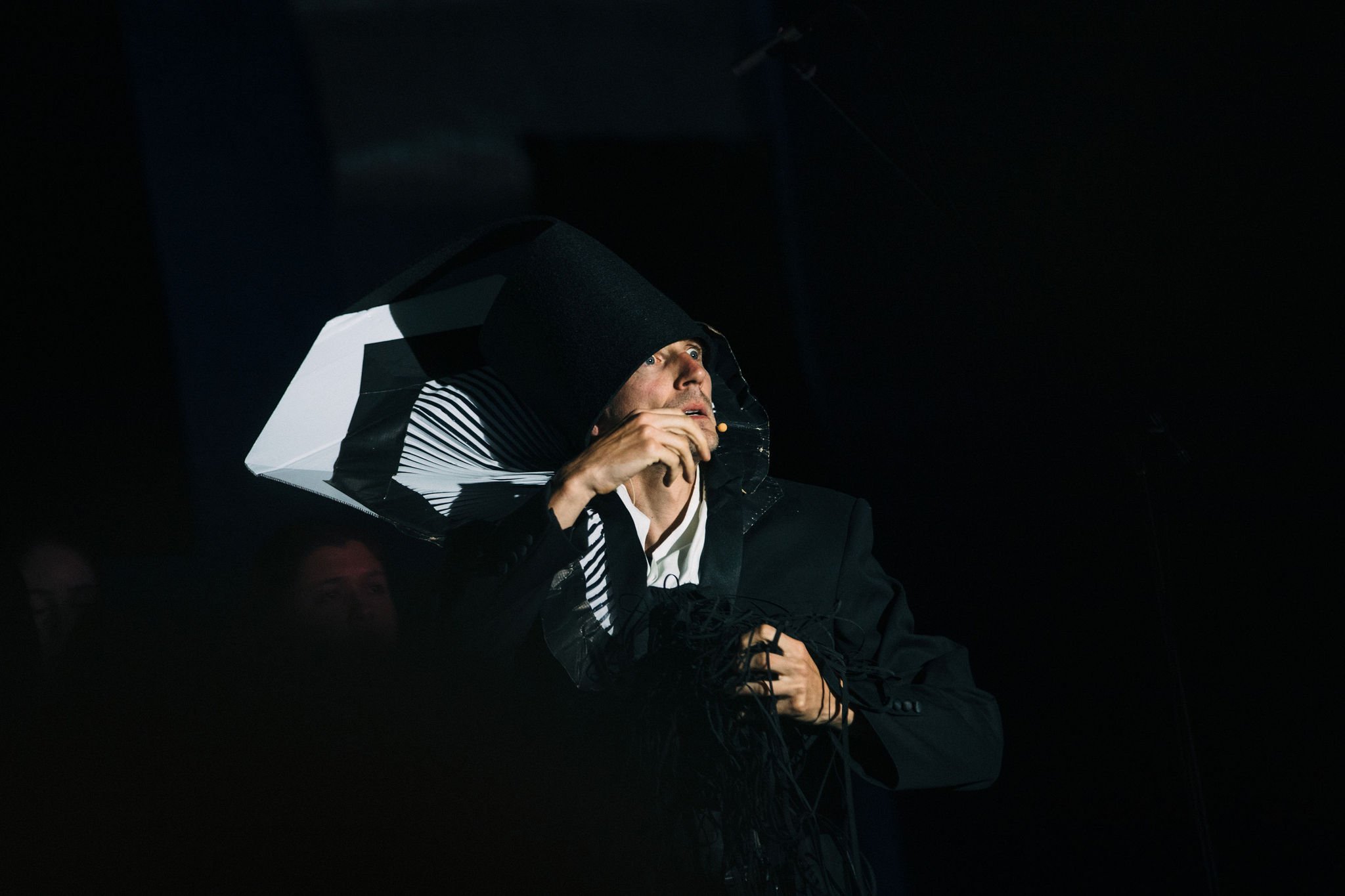

The exhibition leads us through a chronology of sorts, beginning with a series of posters for early gay liberation club gatherings from the late 1970s: ‘Hot ’n Sloppy / Blatant Outrage’ reads one; ‘Tell Me You’ll Come?’ another. The biggest space is dedicated to the biggest parties, including the 1980s Mardi Gras, Sleaze Ball, RAT (Recreational Arts Team) Parties and Sweatbox. There are hand-drawn set designs for the Hordern Pavilion events, the tease of a Stephen Allkins cassette-tape set list for the Dome, and fashions by Martin Harsono, Kathy McKinnon, Mark O’Brien and Billy Yip.

A room designated ‘Dyke Decadence’ showcases lesbian nights, including the radical 1990s women’s takeover of a men’s bathhouse: ‘On the Wet Side’ at Ken’s at Kensington. A screen-printed poster by Anne Sheridan paraphrases the Emma Goldman catchcry: ‘IF I CAN’T DANCE … I DON’T WANT TO BE PART OF YOUR REVOLUTION.’ Nearby, Peter Schouten’s posters for Homo Eclectus showcase their masterful approach to graphic design.

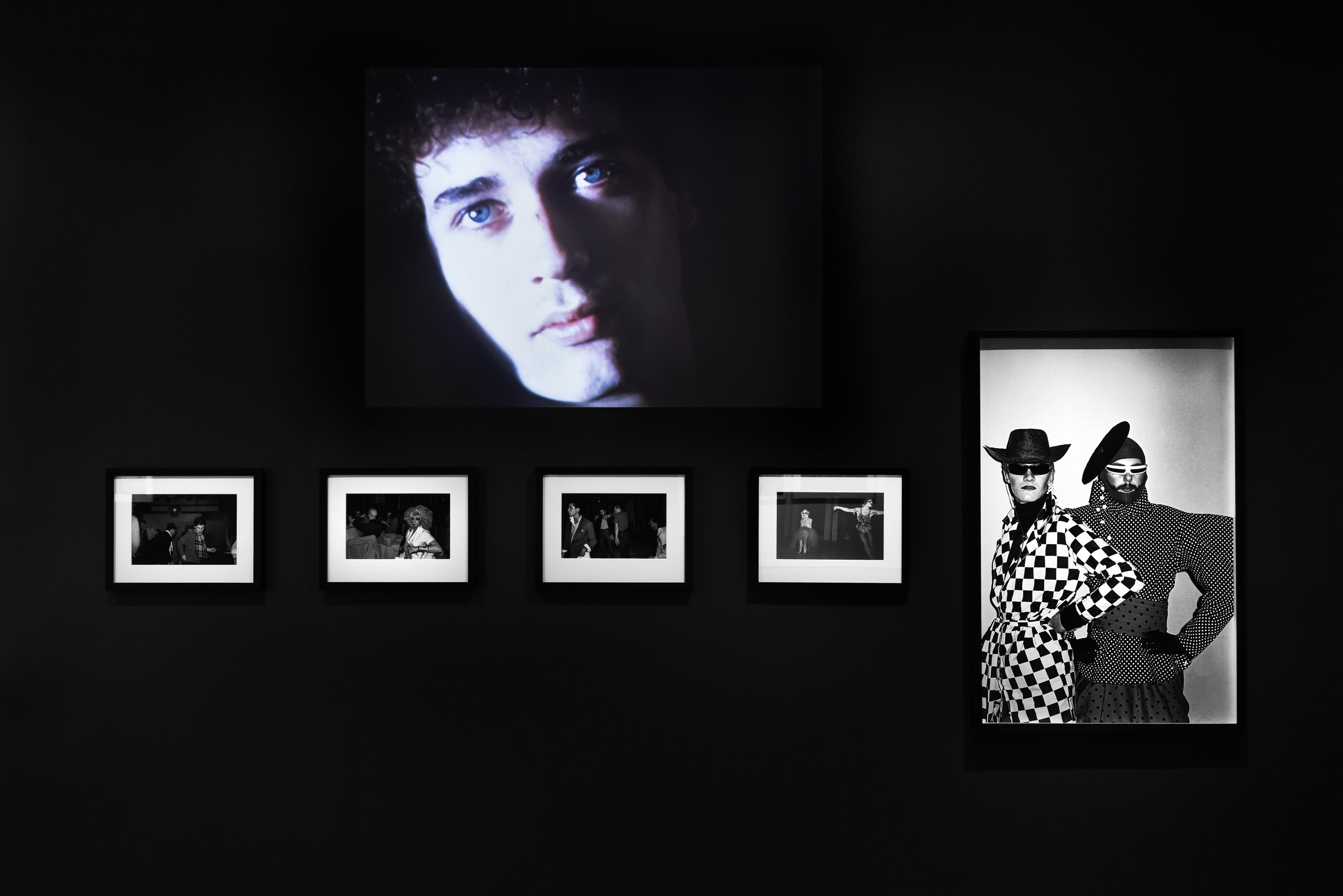

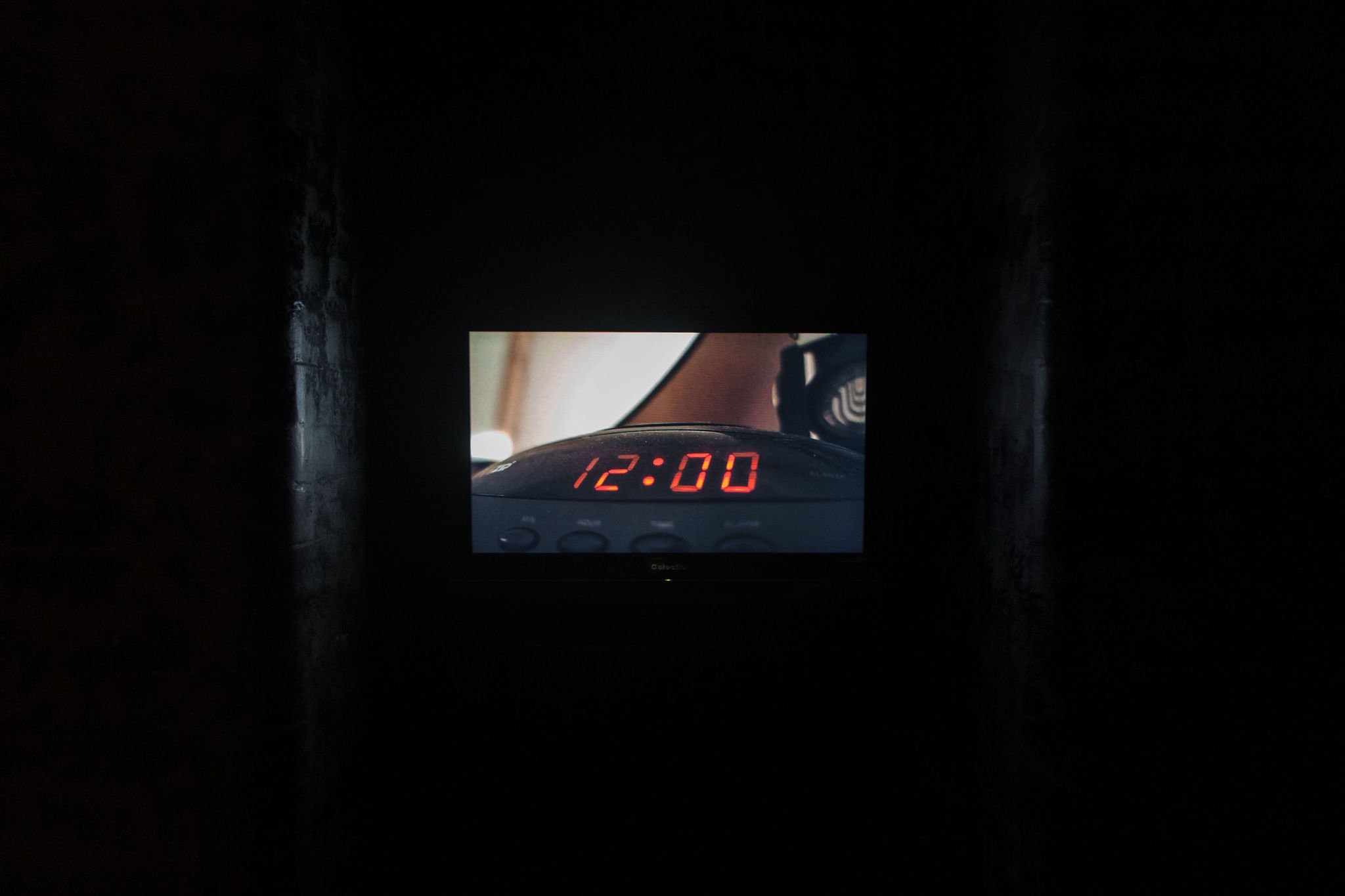

The deepest enclave of the exhibition echoes a darkroom and holds objects of a kinkier nature. There are exquisite scenes captured by Jamie James from Hellfire, Club Kooky, Sex and Subculture and more, alongside posters and photos from long-running leather party Inquisition – events that feel a world away from the saccharine palatability of the parties of ‘Sydney WorldPride 2023’.

Times have changed. Producers here struggle. Artists struggle. We can’t ‘go back’ and nor should we. We deserve something new, something beautiful, and to dance with the ghosts of history as practical, ethical and spiritual foundations for what comes next. And when sex workers organise a queer strip club in an abandoned cinema, when femmes and dolls snap up every ticket to ‘Xaddy’s Boat Party’, when fetish folk gather at the Hide, when a dive bar acquires a new sex-on-premises licence, when the Bearded Tit gets butch on ‘Sad Dyke Sundays’, when Loose Ends heaves, when Arq reopens, and when House of Mince ‘minces’ – it feels like what’s next is already upon us.

Blake Lawrence, Warrang/Sydney

Curated by José Da Silva and Nick Henderson, ‘THE PARTY’ is presented by UNSW Galleries and ‘Sydney WorldPride 2023’ and is being exhibited at UNSW Galleries in Warrang/Sydney until 23 April 2023.