‘Land Abounds’: Considering the breadth and blind spots of art history

/The apricot-pink tower of Retford Park peeks through the foliage as visitors approach the Italianate mansion’s former dairy, now home to the Southern Highlands regional gallery Ngununggula. Built in 1887 by Sydney’s Hordern family of department-store fame, and then the country home of arts patron James Fairfax of the newspaper dynasty from 1964 until his death in 2017, when it was left to the National Trust, Retford Park in Bowral perfectly encapsulates everything the rural enclave an hour-and-a-half’s drive from Sydney has aspired to, with a forest of oaks, spectacular topiary, and art-laden walls within which speak richly of Europe. In fact, Fairfax famously had his dining room painted with murals by Donald Friend in the late 1960s, and over the years gifted a collection of Old Masters paintings to the Art Gallery of New South Wales, including works by Canaletto, Rubens and Tiepolo.

By contrast, the old dairy sits within a meadow of wildflowers, with the only ‘introduced’ element being its Tonkin Zulaikha Greer (TZG)-designed modern annex bearing the gallery’s striking metal sign: NGUNUNGGULA, meaning ‘belonging’ in the local Gundungurra language. Opened in October last year, following a high-profile fundraising campaign led by local artist Ben Quilty and subsequent AU$7.6 million restoration by TZG, the gallery launched with an eclectic program of exhibitions by Megan Cope (Quandamooka), Tamara Dean, curator Djon Mundine (Wehbal) and John Olsen. However, it is with the current season of ‘Land Abounds’, and in particular with new works by artist brothers Abdul Abdullah (born 1986) and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah (born 1977), that Ngununggula really achieves the stated aims of Director Megan Monte to ‘encourage thought and discourse’ and ‘reframe pervasive cultural perspectives’.

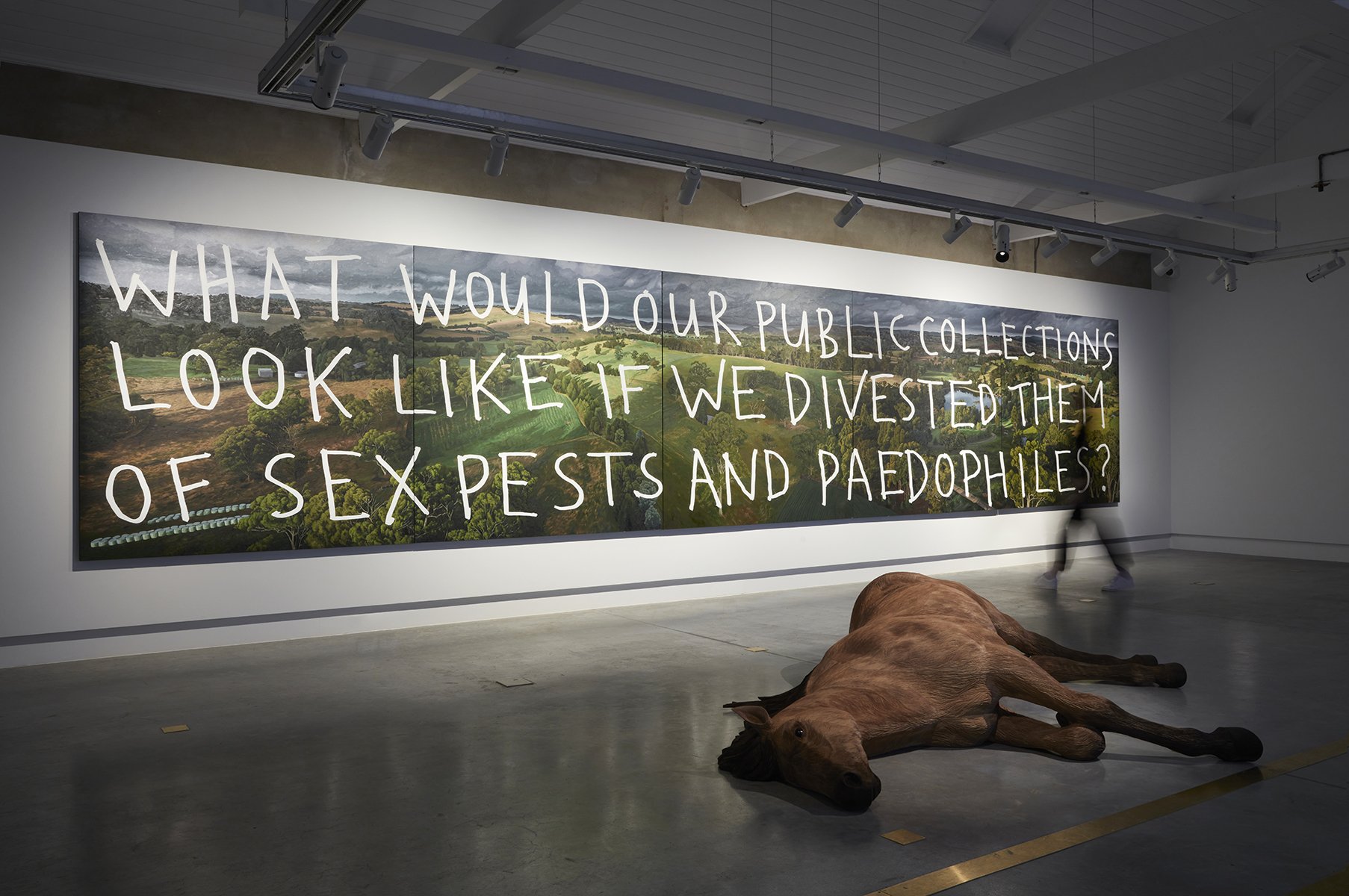

Passing the low audio rumble and high jinks of Tracey Moffatt and Gary Hillberg’s video montage Doomed (2007), audiences are confronted by the fallen figure of a chestnut mare collapsed on the concrete floor. Whittled life-size from Indonesian jelutong timber, Dead Horse is the latest in Abdul-Rahman Abdullah’s series of animal sculptures that switch the spotlight onto the human world that breeds such creatures as pets, playthings or working animals. With the Southern Highlands known for its equestrian hobby farms and Anglophile horse culture, it is perhaps no coincidence that the artist, a seventh-generation Australian Muslim, offers up this animal, with its historical roots spanning North America and West Asia, as a more complex cultural symbol.

But a bigger provocation lies behind this equine figure. Abdul Abdullah’s Legacy assets (also 2022) is a 10-metre painting of neighbouring Berrima, with a bird’s-eye view taking in the Wingecarribee River as it weaves through a pastoral patchwork of green. What is written in white capitals across the land isn’t quite as pretty: WHAT WOULD OUR PUBLIC COLLECTIONS LOOK LIKE IF WE DIVESTED THEM OF SEX PESTS AND PAEDOPHILES? It is a question, but a loaded one, and freighted with the recent noise of the #MeToo movement and call-out culture.

The words hover like birds over the earth, but to experience the work in the flesh is to have the wind knocked out of you, evoking a feeling that is visceral and cerebral as the message hits home. It is not surprising to learn the painting was the product of both historical curiosity and rage as the artist delved into the archive of Australia’s nineteenth- and twentieth-century landscape painters. ‘As I absorbed official and unofficial biographies, memoirs, and diaries I became more and more frustrated with the personalities described,’ he wrote on Instagram. ‘The projection of genius on deeply flawed individuals was used to justify and obfuscate abhorrent behaviour … I asked myself why would we continue to lionise, celebrate and uplift these practices and what contribution to the visual discourse was so essential that we owe these legacies anything?’

Most powerful is what Abdul Abdullah leaves unsaid, naming no names, but encouraging audiences to do their own historical research, to start their own artistic reckoning. The question he asks is a difficult one to answer in the nuanced way it deserves, especially considering the breadth and blind spots of art history, but it is an important one, at this point in time, to ponder.

Michael Fitzgerald, Bowral

‘Land Abounds’ is on display at Ngununggula, Bowral, until 24 July 2022.