Welcome to Issue 331

/This Autumn edition of Art Monthly Australasia springs from my involvement as part of the Curatorium for the 23rd Biennale of Sydney. Along with my insightful and generous peers Paschal Daantos Berry (Head of Learning and Participation, Art Gallery of New South Wales), Anna Davis (Curator, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia), and Hannah Donnelly (Producer, First Nations Programs, Information + Cultural Exchange), I have been fortunate as Curator at Artspace to work alongside Artistic Director José Roca to collectively curate the 2022 edition. Titled ‘rīvus’, it centres around rivers, wetlands, seas and other salt and freshwater ecosystems as dynamic living systems with political agency. These entities have for the longest time been witnesses and victims to our collective mistreatment of the earth and of each other.

In our research we have been led by many rivers and water bodies worldwide and their custodians from all walks of life – two-legged and otherwise – in an attempt to consider a perspective other than our own. I believe this sentiment is really what art is about and that artists are critical in leading social change by opening up hearts and imaginations.

So for this issue I’ve invited artists, writers and curators to respond to the tributaries of thought and ideas behind ‘rīvus’, with a consciously open-ended approach more poetic than political (although the latter is inescapable and the former is often political). A number of the works and practices explored in these pages can be seen in the Biennale. Others share an interest in its delta of interrelated themes, including Indigenous science, cultural flows, ancestral technologies, counter-mapping, multispecies justice, water healing, spirit streams and sustainable methods of coexistence. Rivers, and water more broadly, were ever-present in our conversations, as were their connotations of flow and connectivity.

James Gatt opens with his stream of consciousness, a water-like text ‘intended to meander and flow, to embrace transferral and possible cultivations’. He swims through multitudinous ideas, including the privatisation and control of water as a means to regulate and confine publics – an ongoing colonial and capitalist tactic. Moving from liquid to data streams, from the physical to the spiritual, Gatt is guided by the work of a number of artists, writers, sociologists, neuroscientists and philosophers.

Pondering the consciousness of nature, Wergaia and Wemba Wemba woman Susie Anderson takes inspiration from ‘rīvus’ participant Carolina Caycedo’s evocative water portraits that give water ‘its own form, face, and its own particular voice’. Anderson revels in the watery qualities of empathy, adaptability, ferociousness and determination. She talks to water and listens in return. She shares its warning: be open to confluence, or else!

As is characteristic of the collaborative spirit of their practice, IVI invited their friend and accomplished ocean voyager Captain ‘Aunofo Havea Funaki Satuala to share some of her story. ‘Aunofo is the first female licensed captain in Tonga, chartering traditional vaka across vast seas, and the transformative role that weaving and navigation have had on her life is evident in her generous words.

In concert with ‘Aunofo’s descriptions of her haptic knowledge of sailing and weaving are Madeleine Collie’s somatic memories of her time spent in Folkestone in south-east England. Working with artists in direct response to the site opens up a larger enquiry into, in her words, ‘the task of finding other ways of being human’. In her musings the landslides of the Warren are an expression of the earth, an ‘earth being’, and also an apt metaphor for history, and for modernity, ever-shifting under our feet.

Anabelle Lacroix delves into the diverse practice of ‘rīvus’ participant Clare Milledge (and our cover artist), who encapsulates many of the ideas explored in our pages – collaboration, sustainability, a (re)turn to the poetic, and an acknowledgment and respect for knowledge that is held and known only by the body – of humans, of animals, plants, waters and stars.

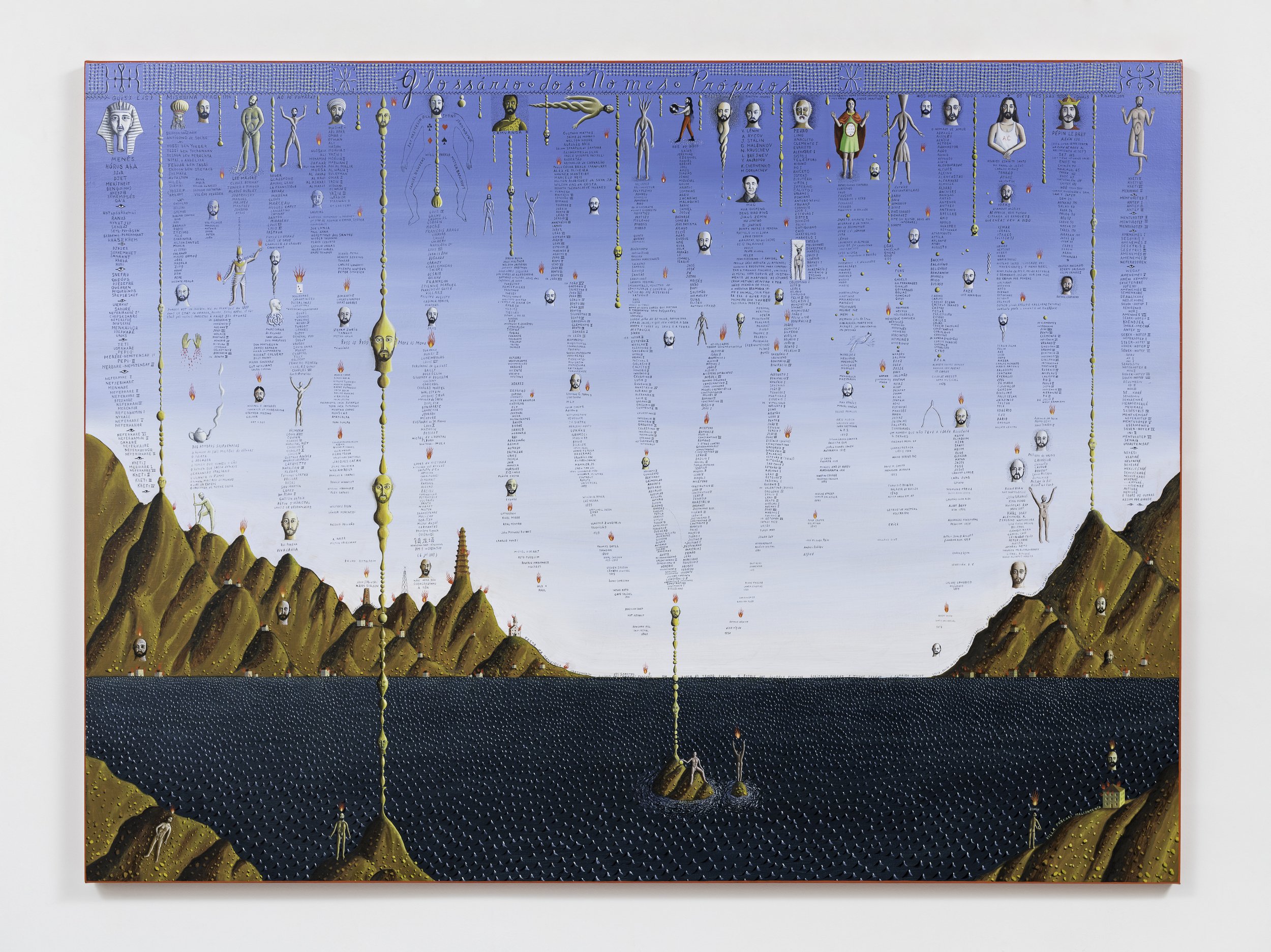

Brazilian artist Alex Cerveny shares his exciting new works commissioned for the Biennale, while Tabita Rezaire reveals Amakaba, her evolving vision for a more conscious and responsible way of living, built in the middle of the Amazon rainforest of French Guiana.

Thank you to the commissioned writers and artists for their wonderful contributions to this explorative issue, and to my truly collaborative and supportive colleagues in the Curatorium and at the Biennale of Sydney and Artspace.

Talia Linz

Guest Editor