Crossing continents and time: Daniel Thomas on the incomparable Christo

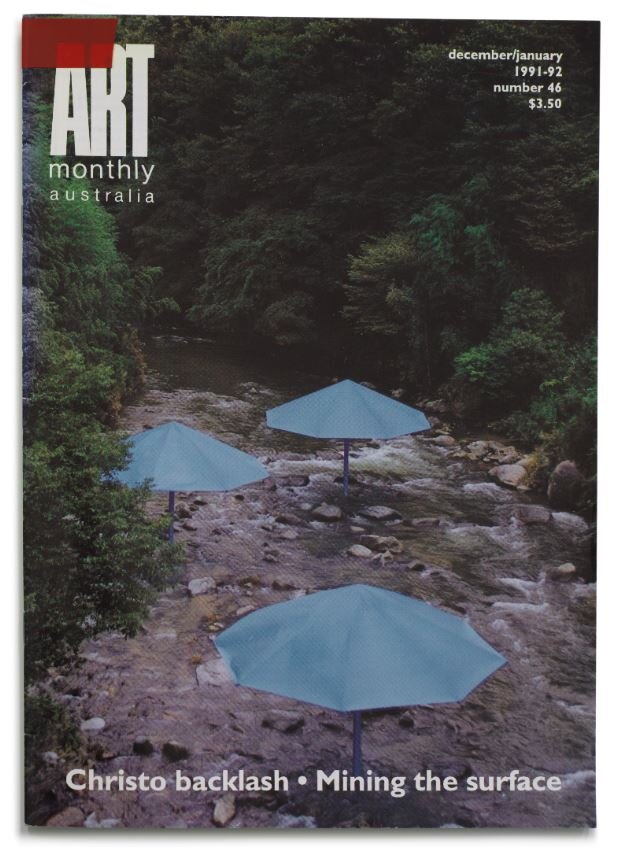

/On 31 May, the Art Monthly Australasia team and many other art lovers across the world were sad to learn that the incomparable Christo Vladimirov Javacheff (1935–2020) had died at his home in New York. By an uncanny stroke of coincidence, while planning our current Winter issue back in March, we had occasion to include an article from our archives by the equally incomparable Daniel Thomas, first published in December 1991 (AMA #46) and dedicated to Christo’s six-year undertaking, The Umbrellas: Joint project for Japan and USA (1984–91).

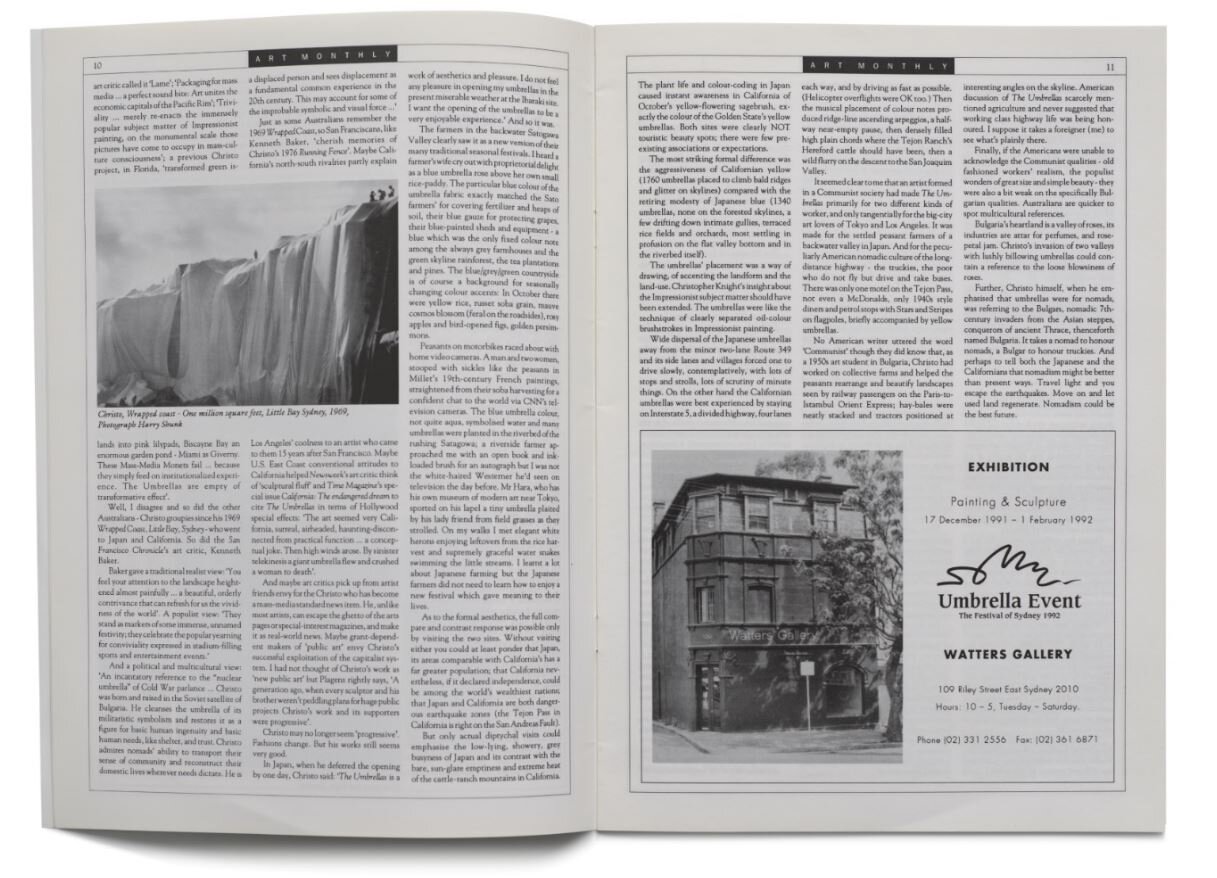

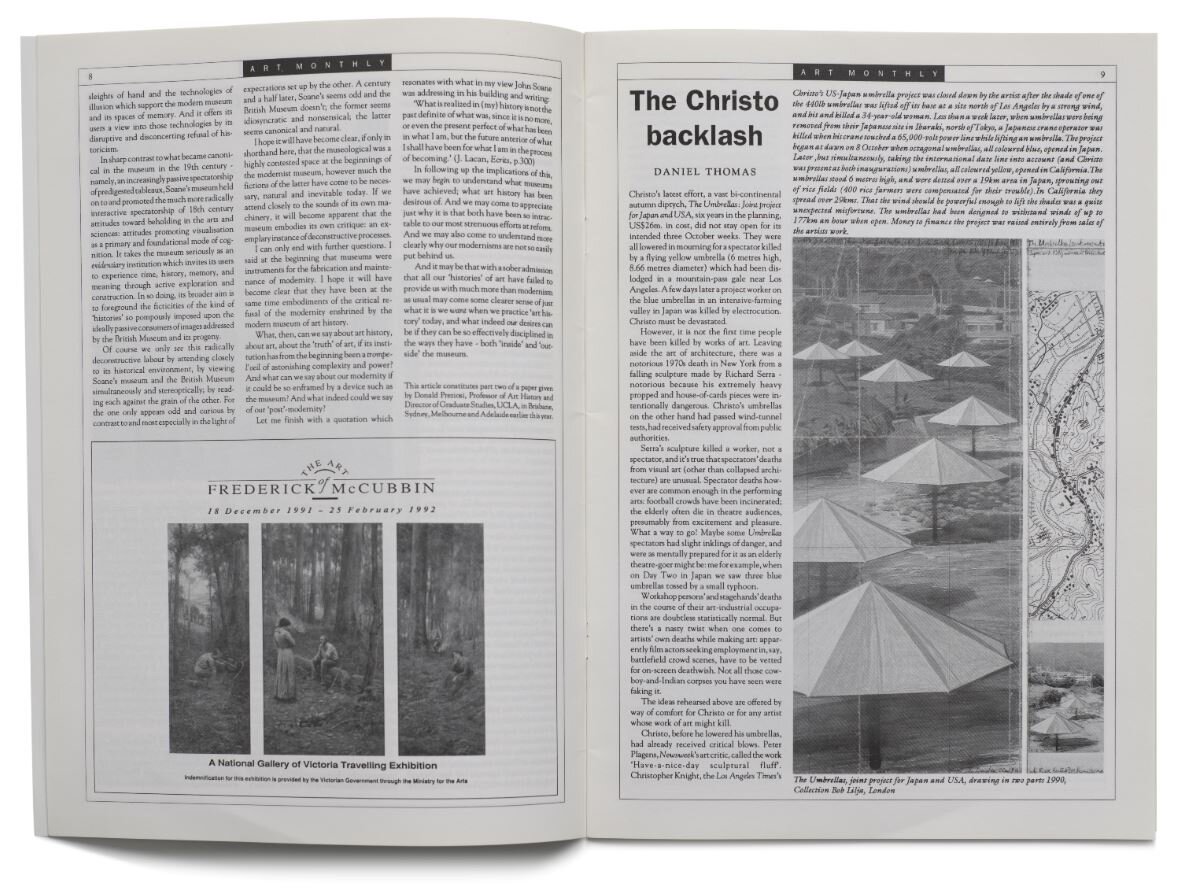

As Thomas makes clear in his recollection of the project’s reception, The Umbrellas wasn’t one of the most successful installations that Christo and his artist-partner Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon (1935–2009) developed over five decades of collaboration. The planned three-week duration of this ‘vast bi-continental diptych’, for which thousands of hired labourers installed 1340 umbrellas in Japan’s Satogawa Valley and another 1760 in Tejon Pass, California, at a cost of US$26 million, was cut short in both locations by tragic twists of fate. In Los Angeles, a spectator was killed by an umbrella caught in a sudden gale, while in Japan one of the workers on the project succumbed to a fatal electrocution. This was despite the exhaustive battery of safety tests and approvals on which the artist had insisted prior to installation.

Even before the early closure of The Umbrellas, Christo faced strident criticism from arts writers at Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times and Time magazine, who accused the artist of pandering to mass appeal. As a self-professed ‘Christo groupie’, however, Thomas refutes these accusations and rescues the ill-fated project from the purgatory of critical disapproval with an erudite reappraisal that illustrates why he is justifiably one of our most beloved arts writers while also demonstrating why Christo, even in the direst of circumstances, remained a consummate artistic innovator throughout his long career.

For Thomas, the public spectacle of The Umbrellas wasn’t its defining or even most distinctive quality: it was the artist’s sensitivity to the settings chosen for his work and the implications of their juxtaposition that set the project apart in the crowded field of global installation art. The blue of the umbrellas in the Satogawa Valley, he writes, ‘exactly matched the Sato farmers’ covering for fertilizer and heaps of soil, their blue gauze for protecting grapes, their blue-painted sheds and equipment’, its watery symbolism suggesting a new addition to the local calendar of seasonal festivities. In California, yellow umbrellas were perfectly suited to the arid desert landscape, shimmer of the sun and vivid blossoms of the sagebrush. For Thomas, these installations indicate a sincere empathy ‘for the settled peasant farmers of a backwater valley in Japan [and] for the peculiarly American nomadic culture of the long-distance highway’. In the joining of these communities he finds a revelation of our shared responsibility for and grounding in the natural environment: ‘Travel light and you escape the earthquakes. Move on and let used land regenerate. Nomadism could be the best future.’

Those who’d like to read more of Daniel Thomas’s canon-defining contributions to the history of Australian arts writing will be pleased to know that 77 of his most influential pieces – including his thoughts on ‘Being a curator’, published in AMA #123 (September 1999) – will be compiled in Recent Past: Writing Australian Art, a magisterial anthology due to be published by the Art Gallery of New South Wales later this year.

Dr Alex Burchmore, Publication Manager