Retooling the conventions of value: An Indigenous perspective at the Museum of Sydney

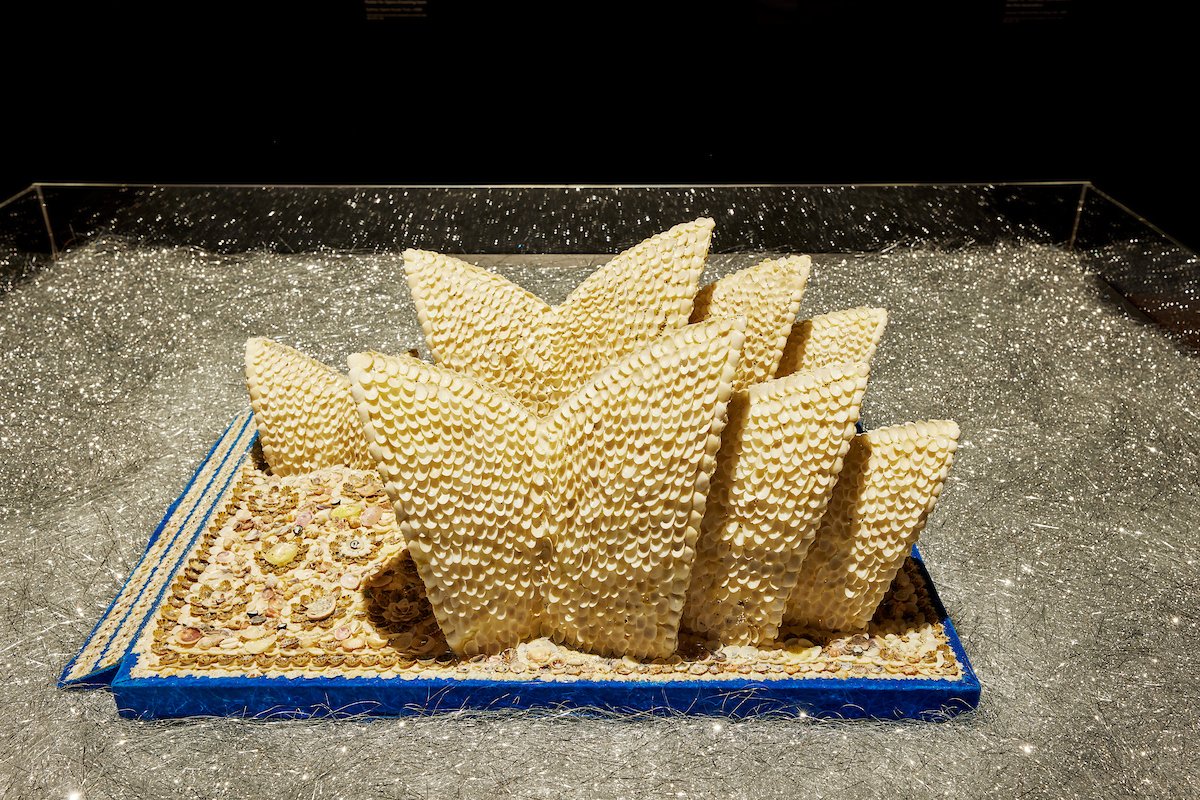

/At the far eastern corner of the ‘The People’s House: Sydney Opera House at 50’, a seductive shimmer of silver glints out from a darkened black-box space. Esme Timbery’s shellworked opera house is a wonder to behold in any context. But here, floating atop a bay of tinsel sparkling under a bright spotlight, it is breathtaking. According to curator Tess Allas (Wiradjuri), the idea for this presentation is one that has percolated over the three decades she has been working closely with the Bidjigal artist. It is a dream manifested and, to my mind, speaks to a much bigger world-building dream – one that not only contests First Nations genocide, but imagines a world in which such contestation no longer requires repetition.

Timbery’s work, commissioned by the Sydney Opera House in 2002 and borrowed by the Museums of History NSW for this exhibition, is flanked by four posters of shows presented at the opera house from the State Archives of New South Wales. The most salient of these features a black screen-printed portrait of Truganini, accompanied by a title in bright red capitals, ‘THE LAST TASMANIAN’, and a subtitle in black, ‘A STORY OF GENOCIDE’. The poster is shocking and demands closer inspection, in which a clever retooling of the object is revealed. To spite its problematic message, the poster was chosen by Allas to illustrate an unbroken, ante-colonial and cross-continental practice of shellwork carried through countless generations of Aboriginal women. Below her arresting gaze, Truganini’s neck is adorned with an abundance of strung shells. The creation of shell necklaces is continued by contemporary shell workers, such as Lola Greeno, who prove the ongoing and thriving presence of palawa women and their cultural practices. Timbery’s shellwork was also passed through generations of Bidjigal women as both a way to continue cultural knowledge and as a means of gaining economic independence. The dialogue created between Truganini’s necklace and Timbery’s opera house, as such, contests the historic and ongoing efforts of genocide, which include the mythologisation of Truganini as ‘the last Tasmanian’ and gives testament to how First Nations cultures survive and thrive through creative practice grounded in Country and informed by savvy contemporary sensibilities.

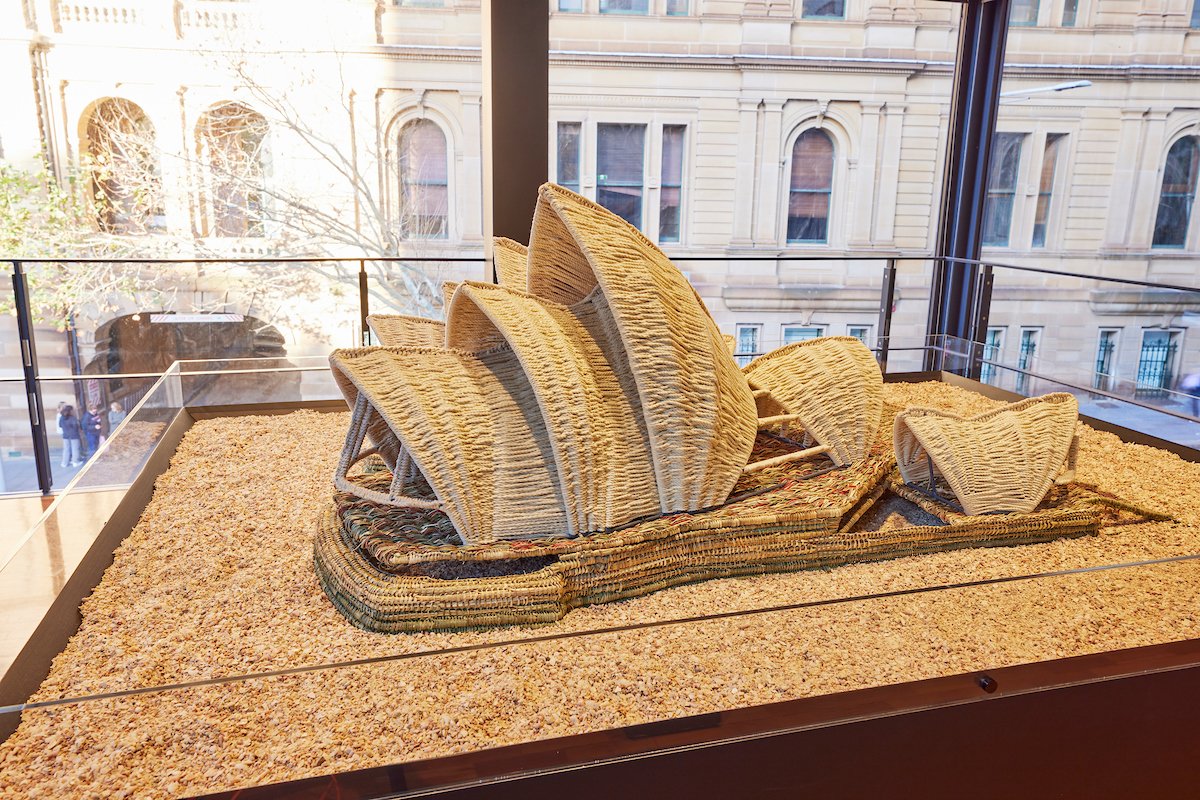

This dialogue continues in the exhibition’s adjacent room. On a bed of shell grit sits a striking woven rendering of the opera house featuring predominantly undyed cotton woven over the sails, and hand-harvested, dyed and woven Lomandra longifolia grass for the base. The work was made by master weavers Steven Russell, Timbery’s son (Bidjigal/Dharawal/Wadi Wadi), and his partner Phyllis Stewart (Yuin/Dharawal), and commissioned for the exhibition. Within the conversation of contesting genocide through cultural practice created through the adjacent room, the woven opera house both nods to and demonstrates the radical work institutions can do in supporting the continuation of such Indigenous practices. This support continues to shift the representation of First Nations cultural practices through contesting conventional exhibitionary traditions and retooling or developing new models. As such, Allas’s commissioning and curation remind us that, without the critical intervention of First Nations curators, museums would still be denigrating Indigenous cultural production as craft, kitsch or, at worst, ethnographic specimen.

The conversation I raise here is old news for those familiar with discourses on exhibitionary models. But the relevance of repetition is clearly demonstrated by the rest of ‘The People’s House’, which presents material in an aesthetic firmly seated in anthropological, archaeological and ethnographic styles. In its first room, for example, a Mei mask from the Sepik River in Papua New Guinea is presented within a clear perspex box typical of conventional museological displays. The aesthetic is not self-reflexive, as we might expect in a post-1990s new institutionalism cultural climate, but earnest. It is this earnestness that worries me. Not only because it is a litmus test for the institution’s relationship with contemporary cultural practices, but also because it indicates the persistence of an ideology harking back to the museum’s history as the site of the first Government House. Museological models that prioritise the display of Indigenous cultural objects as specimens casually reproduce an aestheticisation of genocide. This is not hyperbole. It is for this reason that the use of contemporary art exhibitionary aesthetics by Indigenous curators, especially in traditional museum spaces, is so important. The retooling of the conventions of value developed after the dematerialisation of art, to reinsert and assert value for Indigenous culture, is nothing short of revolutionary.

Given the reported intent to render the Museum of Sydney a First Nations space, I anticipate a difficult conversation ahead as to the ways in which the exhibitionary models of the institution speak to its strategic goals. The interventions of the shellworked and woven opera houses, however, give me tentative hope and I look forward to seeing such curatorial interventions expanded.

Aneshka Mora, Warrang/Sydney

Co-presented by the Sydney Opera House, ‘The People’s House: Sydney Opera House at 50’ is on display at the Museum of Sydney until 12 November 2023.