The seen and unseen in Tony Albert’s ‘Duty of Care’ at Canberra Glassworks

/Tony Albert’s solo show ‘Duty of Care’ is the culmination of a six-week residency at Canberra Glassworks. Glass is a new medium for Albert, known for his work in collage, painting, found material and photography. During his residency, Albert worked with a team of glass artists to produce works that explore the concept of care, the invisible forces that bind us, and the possibility that systemic racism might be shattered with the right force.

Sophia Halloway (SH): Devoid of pigment and inherently fragile, the clear glass used for many of your works in ‘Duty of Care’ makes for a particularly radical medium with which to discuss the polemics of colour. In one work, Uncodified (which way same way) (2020), you have etched the words ‘Invisible is my favourite colour’ into the glass. How has this idea of invisibility come to resonate so strongly in your practice?

Tony Albert (TA): The tension between visible and invisible has always been a core theme of my work. When I was invited to participate in the residency, it took quite a while to investigate how my practice could translate into glass. I had a vision, very early on, that if you looked through the window at the show, you couldn’t even see it. I wanted to somehow produce an invisible show. It was an amazing journey to work with the technicians at the glassworks and to discuss the possibilities of clear glass in exploring the seen and the unseen.

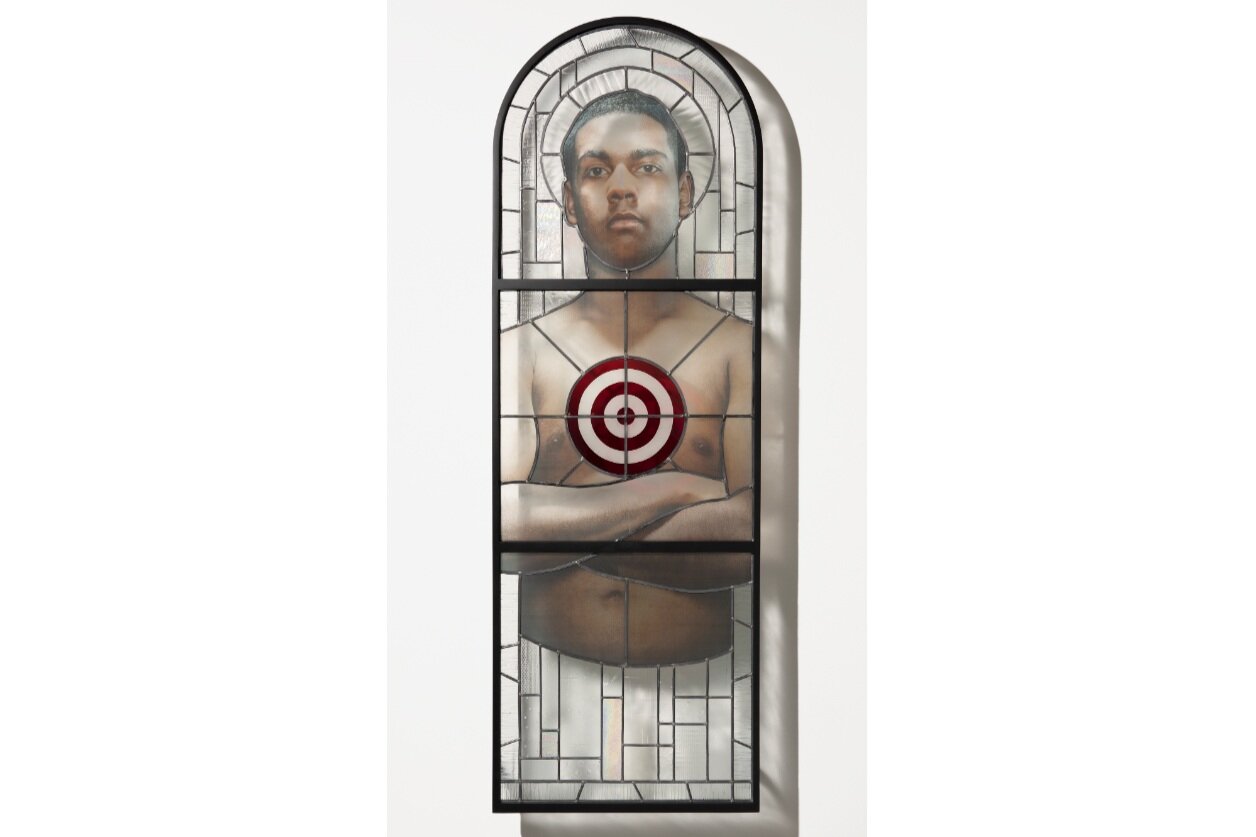

SH: Brother (The invisible prodigal son) II (2020) is a stained-glass window featuring the image of a proud young Aboriginal man with a target on his chest, a recurring motif in your work since the police shooting of two Aboriginal boys in Kings Cross in 2012. Recently, the killing of George Floyd in the United States has reignited discourse not only on police brutality but also monuments to contested histories. What do you think is the role of these images in reclaiming the histories of Indigenous Australians?

TA: Memorialisation is something I think about quite a bit. Not only do we live in a landscape that is so barren of Indigenous indicators, but there’s an abundance of memorials to dead white men. How might our mindsets change if our children walk into a park to find Aboriginal heroes represented, women represented? For me, it’s not so much about pulling things down but about historical truth being shared and opportunities for a more important discussion about history. Stained glass has been used to tell stories throughout history but was only ever afforded to rich institutions such as the church or the monarchy. You rarely see these images of people of colour, or women, so I think there’s a subversion in being able to do that.

SH: Language features heavily in your practice and in ‘Duty of Care’. Seemingly innocuous phrases become loaded with meaning once their histories come to light. What do you say to the symbolic power of language, and what is the relationship between language and care in your work?

TA: Vernon Ah Kee has always said: ‘English is my second language; I just don’t have access to my first.’ I think that’s a particularly poetic way of describing the impact of colonisation, but also how we need to consider language. Contemporary culture has seen language evolve with text and shorthand, with the way we translate symbols and images into a word or feeling. I’m fascinated with language and particularly the written word because we can use it in our favour to challenge ideas and ideals about power. For example, Destiny Deacon leaving the ‘c’ out of Blak, or the capitalisation of Black and White – it becomes a state of being, not just a colour. All of these plays become intrinsic to our understanding, a way we can protest every day just in how we converse with each other.

Sophia Halloway, Canberra

Curated by Sally Brand, ‘Duty of Care’ opened at Canberra Glassworks on 13 June for an extended run until 27 September. Sophia Halloway is a 2020 Critic-in-Residence at ANCA, Canberra, in a special project partnership with Art Monthly Australasia supported by artsACT.