Women’s work

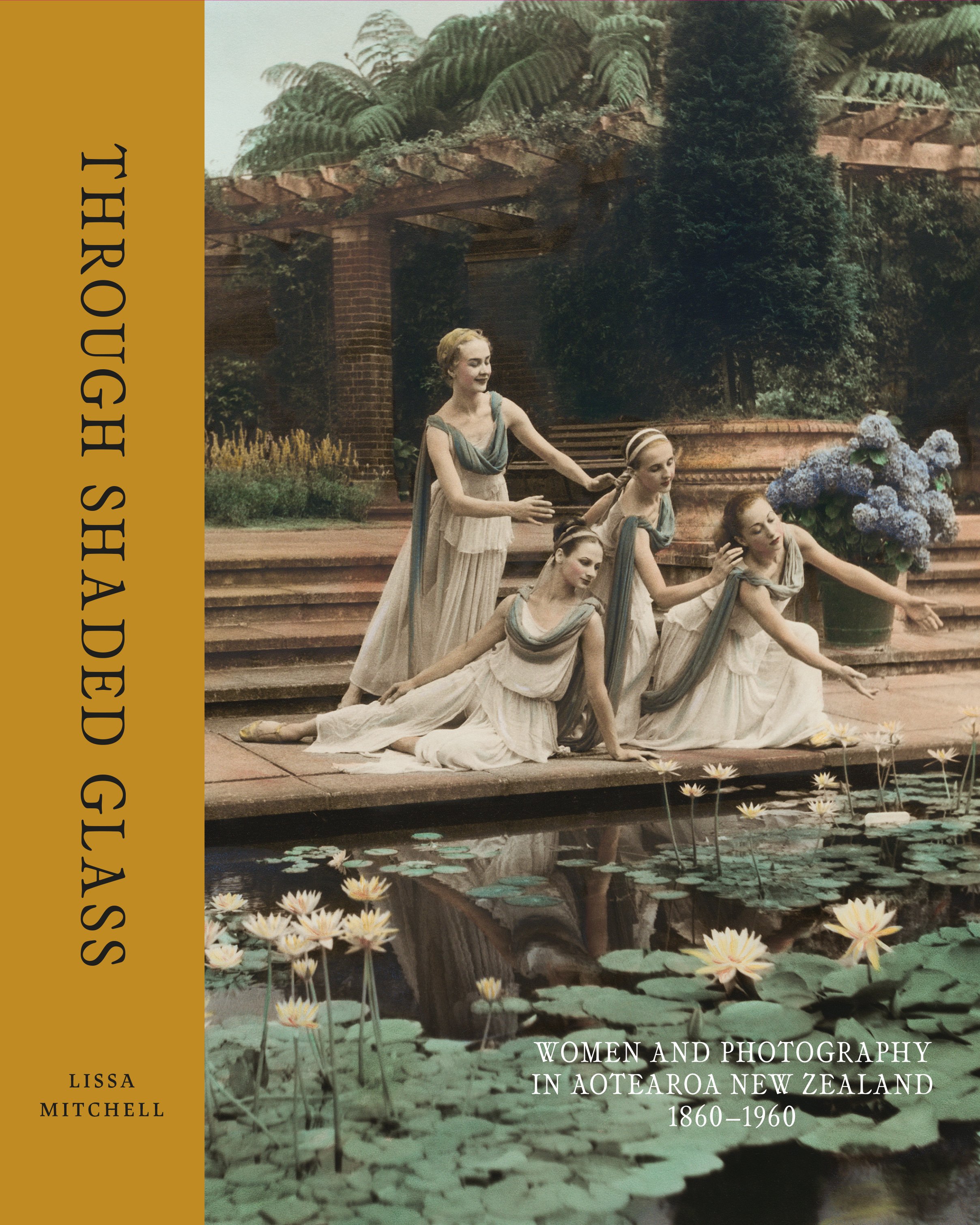

/What is promised by exhibitions and books devoted exclusively to women practitioners? That work and artists that have previously been ignored or neglected will be acknowledged and celebrated? That the reasons for this neglect will be highlighted and condemned? That something specific to the gender of the makers will be identified in the stories of their careers, or even in their work? That the history of art being offered will be distinctively different from those without this particular focus? Through Shaded Glass, Lissa Mitchell’s assiduously researched and beautifully illustrated new book about women photographers in Aotearoa/New Zealand, carefully negotiates all these implied promises. Her project is described by the author as ‘revealing a multifaceted community of photographic production that shows who the women were, how they were involved and what factors enabled, prevented and limited them.’ This revelation is ably fulfilled.

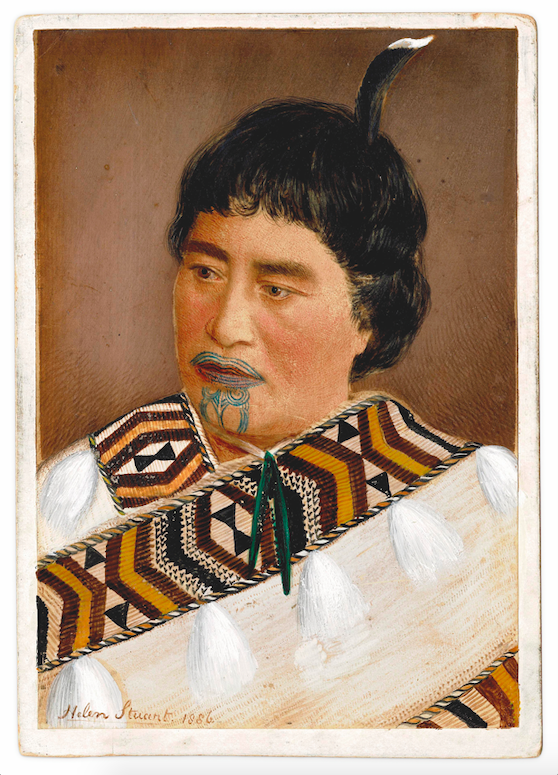

The book begins in the 1860s, when professional studios became firmly established in New Zealand, and finishes a century later, just before photography blossomed into a fine art in which many women were prominent. Mitchell organises her research into a series of chapters that proceed both chronologically and according to genres of practice, so that we learn about the role of women in professional studios but also in the world of amateur photography and clubs and societies. Much emphasis is placed on the business of photography, and for good reason: in the first few decades, far more women worked as mounters, retouchers or printers than as photographers. These are the women who have hitherto remained an invisible presence in histories of photography. Mitchell briefly traces the modernist version of that history, which she concludes has led to the privileging of male artistic figures and unmanipulated photographs. She argues that: ‘the skills employed in retouching, colouring, printing and mounting photographs became characterised as feminine roles associated with other activities done by hand, such as needlework, and [as a result were] increasingly devalued.’ This kind of denigration is revisited in later chapters. As Mitchell tells us, genres like portraiture, photojournalism and architectural pictures, the ones ‘in which most women involved in the medium work’, are ‘precisely those that have been marginalised in the histories of photography in Aotearoa’. Sexism is thereby shown to be systemic, not just a matter of personal prejudice.

To discover New Zealand’s women photographers and their stories, Mitchell has scoured a wide range of sources, including electoral rolls, classified advertisements, legal documents, street directories and newspaper stories. A similar degree of diligence was required to find the photographs that illustrate this book. They come from regional and private collections, as well as from Te Papa’s own capacious archive. But some of these illustrations are digital positives from surviving negatives, or are reproductions of images known only from their publication in vintage magazines or newspapers. As a consequence, we are provided with an illuminating array of hitherto unfamiliar pictures, from hand-coloured and embroidered photographs to album pages filled with still-life compositions to a variety of professional portraits or landscape views. Vernacular examples dominate but women also produced some notable artworks. A particularly striking image is a pictorialist work by Beatrice Mabel Gibson titled Winter Night and dated to about 1920. The photograph was exhibited widely, in both New Zealand and Australia, and much praised in the photographic press of the time. However, only one print has survived to the present, a gift by the photographer to a woman peer. Another example of pictorialism is the hand-coloured silver gelatin print titled Fire, made by Elin ‘Elfie’ Ralph in about 1929, and primarily comprised of a red-tinted haze of threatening smoke. These exceptional examples of photographic artistry are joined by a multitude of less innovative portraits and landscapes, proving that women practitioners were just as capable of bread-and-butter commercial work as their male counterparts.

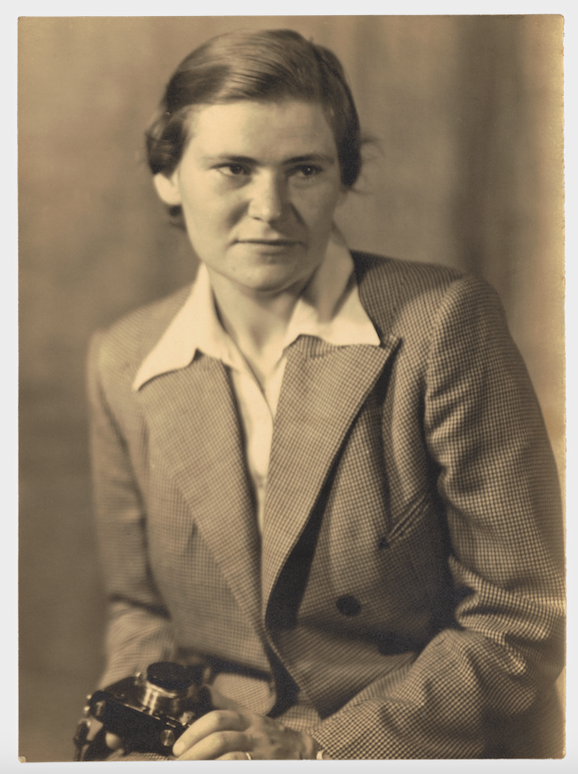

In Through Shaded Glass, photographs tend to be described rather than interpreted. This is in keeping with the heavy emphasis the book places on the social context provided by biography and anecdote. We are told, for example, about an explosion that occurred in Dunedin on 17 May 1886 that resulted in rocks falling through the ceiling of the London Portrait Rooms, killing sisters Julia Finch and Louisa Irwin, who both worked there. Or we learn about the sexual harassment experienced by Minnie Hooper and Mary Ann Allison in 1888 while they worked at a factory that manufactured dry-plate glass negatives in Christchurch. The employment of all these women in the photography industry would be lost to history but for the legal traces left by their travails. Even more revealing are the stories of Austrian and German refugees from Nazism who arrived in New Zealand in the 1930s, some of them accomplished photographers. Irene Koppel, for example, settled in Wellington in 1937, at first working as a printer, before getting a job using her Leica to make candid portraits in the street. As a German Jew and therefore a suspicious foreign national, Koppel was, from October 1940, prohibited from possessing any camera without special police permission. Her marriage in February 1943 was considered sufficient reason to have that permission withdrawn (as, it was argued, she no longer needed to support herself). Mitchell recounts a number of similar stories about such women, a reminder of the obstacles that had to be overcome for these displaced harbingers of European modernism to practise their craft in Aotearoa.

Mitchell’s research makes it plain that women have always played a central role in New Zealand photography, as workers, photographers and clients (the book is enhanced by numerous photographs of women, including several self-portraits that showcase the skill of those taking them). By focusing on the lives of these women, Through Shaded Glass in effect offers a social history of the country in which they worked, at least as one half of the population experienced it. In the process, the book also documents a cavalcade of photographic practices usually ignored by other historians, including those conducted in the darkroom or the office rather than just behind a camera. The end result is an essential supplement to more conventional, more masculine, histories of photography, wherever they have been produced.

Geoffrey Batchen

Through Shaded Glass: Women and photography in Aotearoa New Zealand 1860–1960 by Lissa Mitchell: Te Papa Press, Te Whanganui-a-Tara/Wellington, 2023, 368 pages, NZ$75; Geoffrey Batchen is Professor of History of Art at the University of Oxford.