The ecology of Rachel Theodorakis

/‘Journeys’ at Grainger Gallery, Canberra, features Sally Simpson and Rachel Theodorakis, whose works resonate with bones, mortality, time and thread. ‘Journeys’ is an early commercial show for Theodorakis, who graduated from the ANU School of Art & Design in 2017, and also serves as a survey of her practice to date, with fresh presentations of key works intermingling with new series.

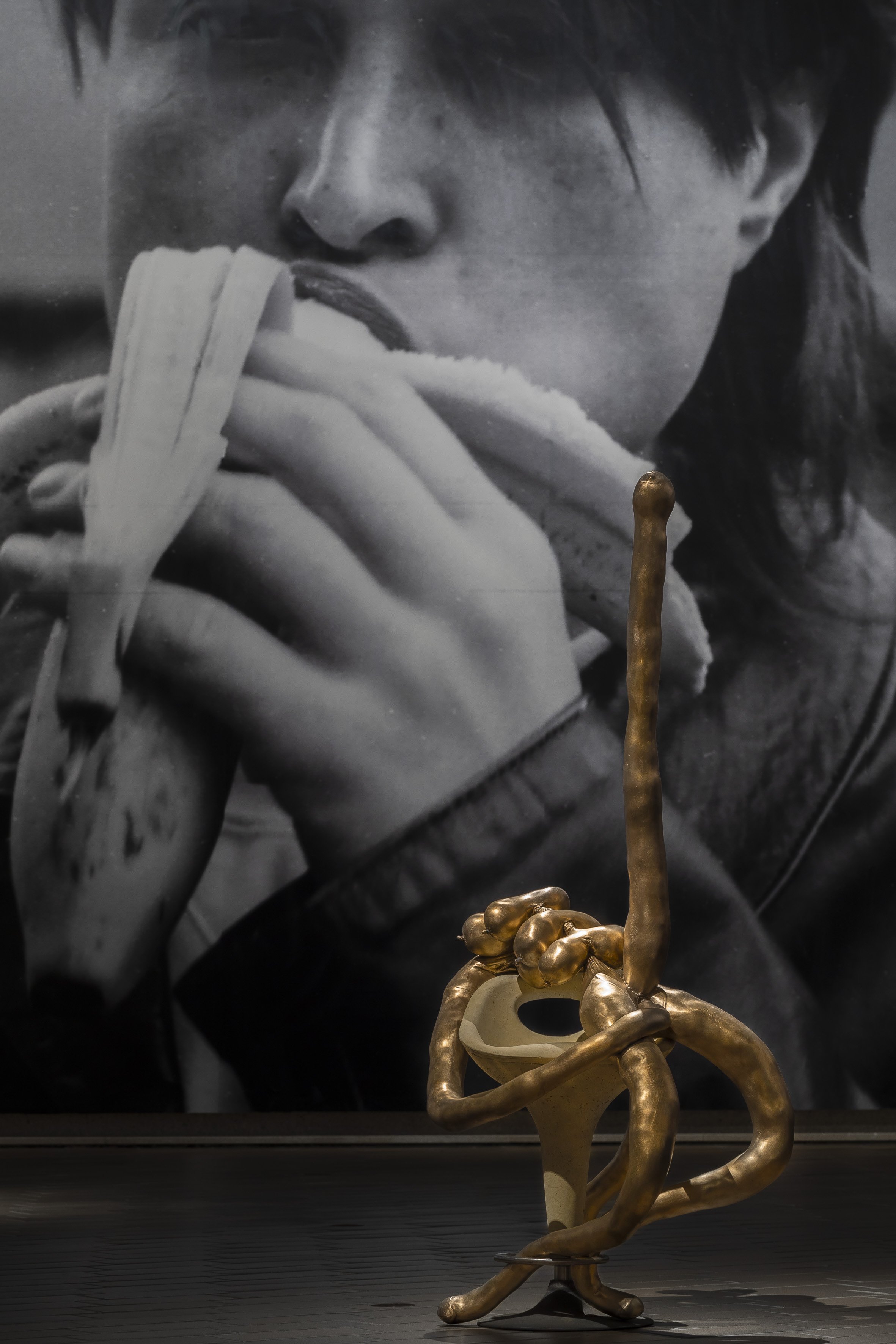

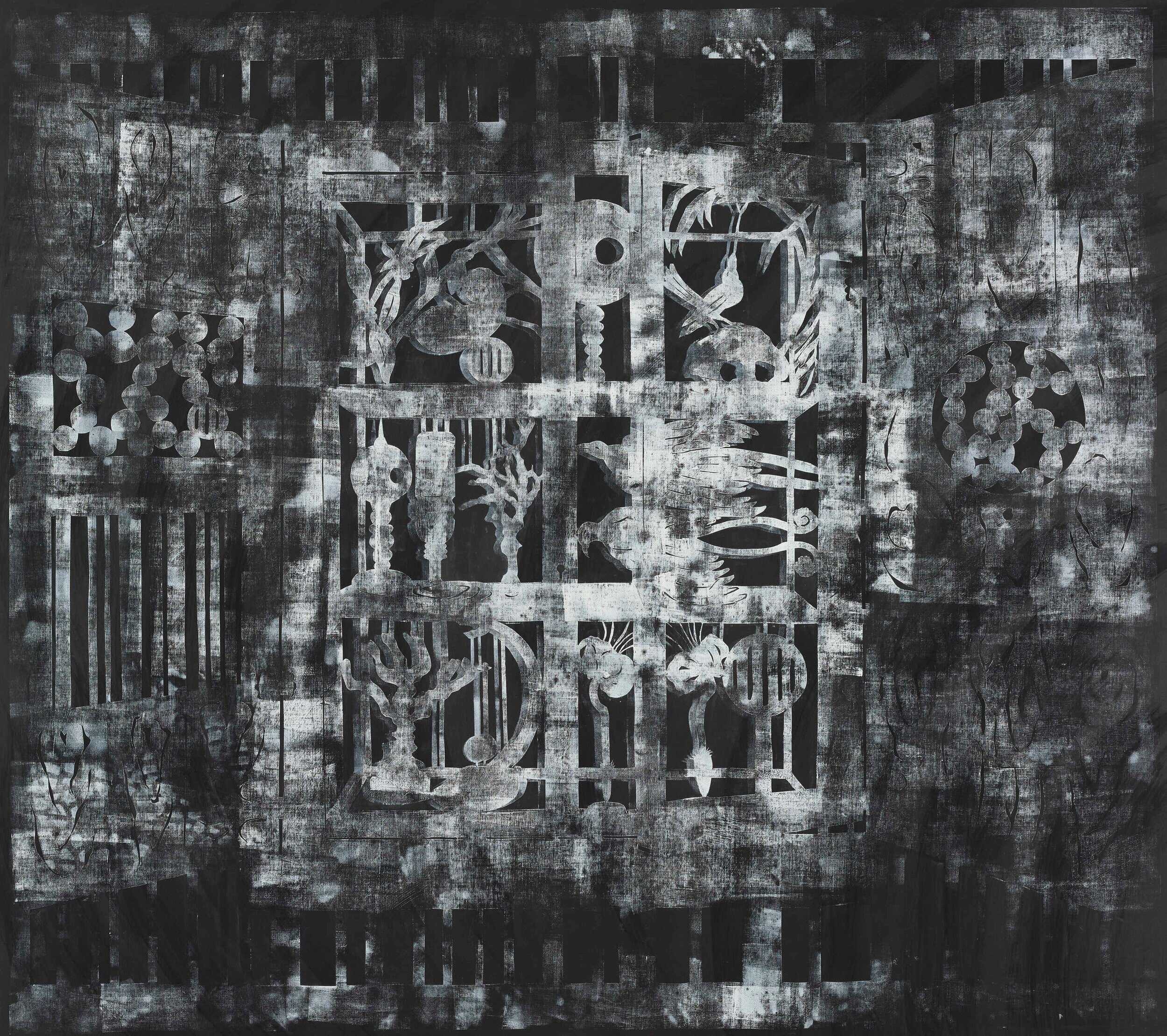

For Theodorakis, tradition proves mutable and expansive. Meditative hand skills learnt from her mother and grandmother are used to graft silk flowers to animal skulls and spines. The art of basket weaving has been refined to encase large curving bones of cows and the finely articulated remains of kangaroos. In this way, the Roman god of beginnings, endings and transitions has become Januss – Goddess of Transitions (2021), embodied by two ram skulls, the forward facing of which is resplendent in a headdress of silk roses. In Transference (2017), a large jawbone is partially clothed in black weaving that suspends a second bone, whose uppermost reaches are similarly covered. Each is vulnerable: the giving, supporting jawbone is being drained; the receiving bone is utterly dependent and unprotected against the time when the jawbone lets go.

Very recent works focus on relationships and wellbeing. The unabashed and unsentimental ‘Nurture’ series of 2021 is a compelling statement of the importance of the parent-child relationship. Each sculpture comprises two resonant forms: a cow bone encased in thick weaving shelters or supports a smaller similarly shaped kangaroo bone covered in finely woven thread. In contrast to Transference, the effect is of connected independence.

In Twentytwenty (2021), the individual bones of a kangaroo tail are each encased in two layers of weaving before being drawn into a gentle encircling darkness. As Theodorakis explained in her artist statement: ‘We live in a society that fears darkness and it causes great distress. I wish to share a different viewpoint … The darkness is a place of nourishment. It offers respite, somewhere to reflect, to gain new knowledge and grow strong again.’

Faced by a world of upheaval and the increasingly oppressive reality of our climate crisis, Theodorakis’s work issues a personal invitation to change. Her careful material transformations suggest that successful transitions are conscious and painstaking as well as intuitive and hopeful leaps of faith. In ‘Journeys’, her work helps guide our philosophical focus – to the darkness for the benefits that can be found there, and to each other.

Margaret Farmer, Canberra

‘Journeys: Sally Simpson and Rachel Theodorakis’ is on view at Grainger Gallery, Canberra, until 20 March 2022.