The importance of narrative sovereignty

/‘Indigenous peoples are the First Peoples of this country. We have a right to be shown.’

– Gail Mabo

First and foremost, I am the sum of my ancestors, hailing from ancient lineages of the Gurindji/Malngin, Pertame Arrernte and Worimi nations of the continent of Australia and the Baloch people of the Middle East. My skin name is Mpetyane. This is my identity among my people, one I share with all other Mpetyane. It determines my relationship with Altyerre, our creation story, and with everyone and everything around me. I state this here because my cultural heritage and identity are crucial to my work as a filmmaker.

I am the co-founder and creative director of GARUWA, a wholly Aboriginal-owned creative agency dedicated to sharing First Nations culture and stories in the right way, with community at the fore. The films that I produce follow protocols around cultural safety that draw on ancient traditions of respect, relationality and reciprocity that are embedded in my diverse lineage—and in many First Nations cultures. I feel a deep responsibility when translating First Nations art and culture to the screen. Indigenous peoples have been stereotyped and subject to bias, misrepresentation and cruelty in media going back centuries. The media has played a huge role in shaping narratives that have championed colonial perspectives, and justified violence and dispossession. But running counter to this dark history is another story: the long tradition of Indigenous artists and storytellers pushing back against colonial narratives and setting the record straight, in their own words.

Both our own people and wider audiences need to understand and experience First Nations perspectives and worldviews. Narrative sovereignty—having the power to tell our own story on our own terms—is integral to this. There is no one better placed to tell our stories than us. Without a deep understanding of the nuances of Indigenous cultures, there is a risk that stories about First Nations peoples will fall into the trap of being clichéd, extractive and exploitative—as much media representation of Indigenous peoples has been throughout history.

I am currently working on a series of 14 short documentaries, one about each of the First Nations artists who were commissioned by the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain to make new work for the 24th Biennale of Sydney. The opportunity to document the incredible work of these artists from across the globe is exciting, but it is also nerve-wracking, as I have a duty of care to each of these individuals and their unique creative practices. Telling an artist’s story through film is no easy task. An artist’s work is the ultimate representation of their identity, their creative response to their experience of the world around them. One of the big questions facing me with this project is: how can I translate these artists’ creative talents to the screen?

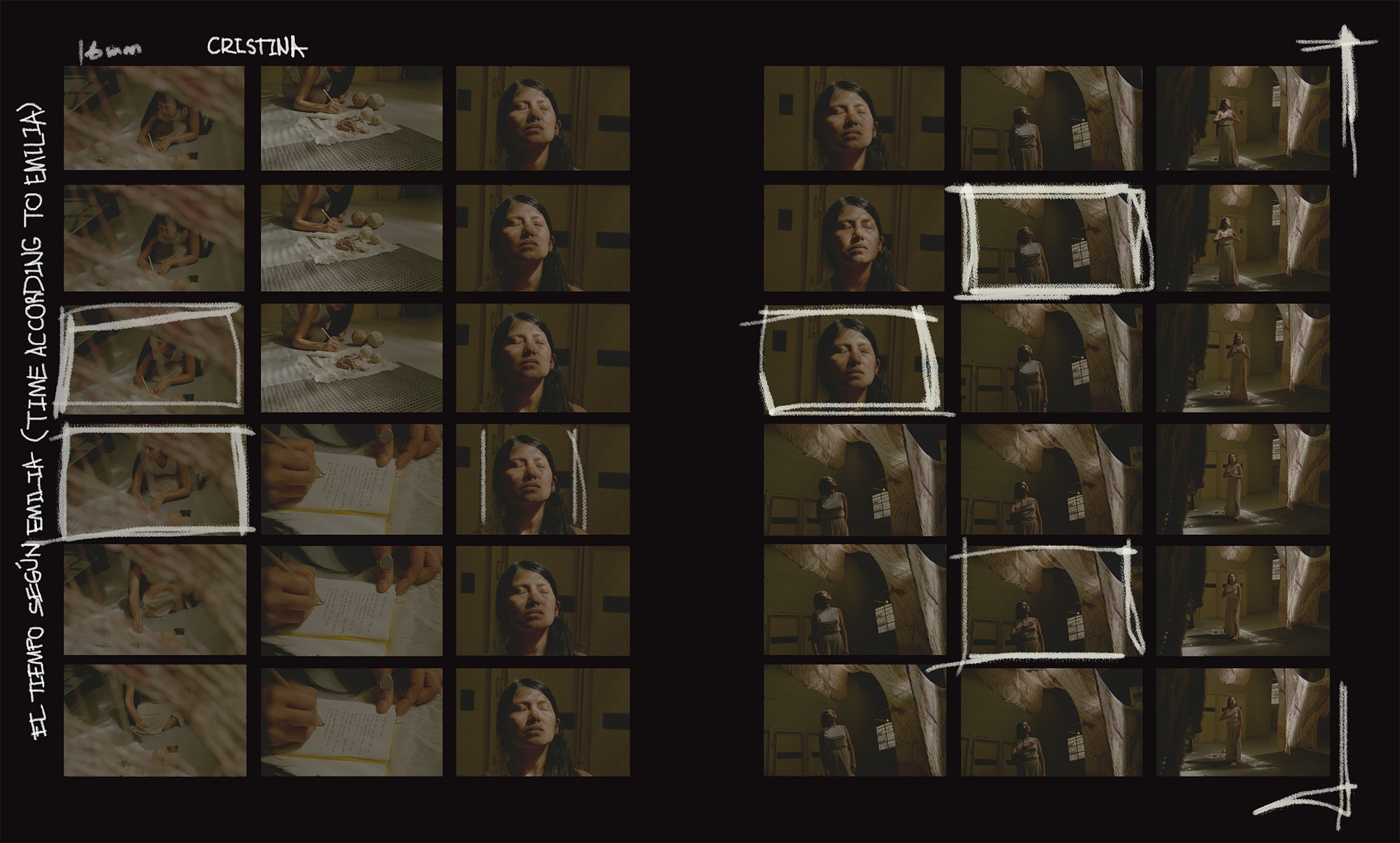

Another question I had was: how can I accurately and respectfully capture and communicate each of the artists’ cultural traditions? The artists come from around the world. Among them are Cristina Flores Pescorán, whose work is inspired by Peru’s Indigenous Chancay culture; Baiga artist Mangala Bai Maravi, who is based in central India; and Dylan Mooney, a Yuwi, Torres Strait and Australian South Sea Islander man, to give some idea of the diversity of First Nations cultures represented. Going into the project, I had knowledge of some of the artists’ traditions, but not all—yet it was my responsibility to capture them all on film.

With that in mind, I began the process of making these films with intentional relationship building. I exchanged details of positionality, personal stories, cultural tales and more with the artists, allowing our relationships to evolve naturally and organically. A good yarn creates an opportunity for connection before the cameras start rolling, which results in the sharing of more meaningful stories. The making of these films has reaffirmed my belief that, while our contexts are not the same, there exists a deep camaraderie between Indigenous peoples around the globe. There are commonalities between us, including shared experiences of resistance, a commitment to the revitalisation of our cultures and a belief in the power of storytelling to improve the plight of our peoples. It has been a privilege to learn about these artists’ perspectives and artistic processes from a position of intercultural understanding. I feel honoured that they have all placed such great trust in me to tell their stories.

This anthology of documentaries we are producing is a co-production between GARUWA and our friends at Entropico, an international production company. The films are being made by a diverse team of creatives, including one of Australia’s best cinematographers, Tyson Perkins (Eastern Arrernte/Kalkadoon). Tyson and I chose to shoot in various formats—Super8, 16mm and digital—to create a visual language that spoke to the artists’ diverse voices, as well as the myriad histories and traditions upon which they draw. We have involved the artists in the creative process from the beginning to ensure that they have ownership of their stories. This collaborative process has resulted in a wonderful series of films. I cannot wait to share them with the world.

Kieran Mpetyane Satour (Gurindji/Pertame/Worimi)

Kieran Mpetyane Satour’s documentaries about the First Nations artists commissioned by the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain to make work for the 24th Biennale of Sydney will be released later this year.

This article was originally published in Art Monthly Australasia’s special edition about the 24th Biennale of Sydney. Purchase a copy here.