What is ‘Wilderness Ideology’ and why is it problematic?

/Wilderness Ideology has emerged from the fields of land management and conservation, but its effects are seen and felt in the arts. In short, it’s the idea that true wildernesses are untouched by people and should largely remain so. In the context of conservation organisations, this does not seem like a bad thing. However, it can lead to an overemphasis on landscapes being vacant, effectively removing people—especially First Nations people, who have lived on and cared for Country for millennia—from the picture, even if we are still present. It’s a contemporary expression of terra nullius.

In 2012, Professor Marcia Langton addressed the subject at length in ‘The Conceit of Wilderness Ideology’, a talk she delivered as part of the Boyer Lectures series. Langton explained: ‘Aboriginal land is targeted both by mining companies and conservation campaigners precisely because it is Aboriginal land. These vast areas owned by Aboriginal people are the repository of Australia’s mega-diversity of flora, fauna and ecosystems because of the ancient Aboriginal system of management, and because Aboriginal people fought to protect their territories from white incursion. They are not wilderness areas—they are Aboriginal homelands, shaped over millennia by Aboriginal people.’

In the art world, Wilderness Ideology can be seen in the contemporary art market’s positioning of Country as something of a “Dreamtime” place. Today, there is the expectation that Indigenous artists will portray Country, but there is not always a proper understanding of the reality that First Nations artists actually live on Country and are intrinsically connected to it. These misconceptions of First Nations peoples’ relationships with their homelands are rooted in the history of the forced displacement of Australia’s Indigenous people from their Country and on to missions, reserves and stations.

Coming from Mapoon, and being a Teppathiggi and Tjungundji man from the Western Cape of Cape York, my own lived experience as an artist has shown me the immense importance that Country and on-Country practices bear in our daily lives. Today, a number of Cape York-based First Nations artists are challenging the art market’s framing of Indigenous peoples—especially artists—as spectators of Country, rather than part of it. They are doing so the way our people always have: by remaining, and by showing we remain.

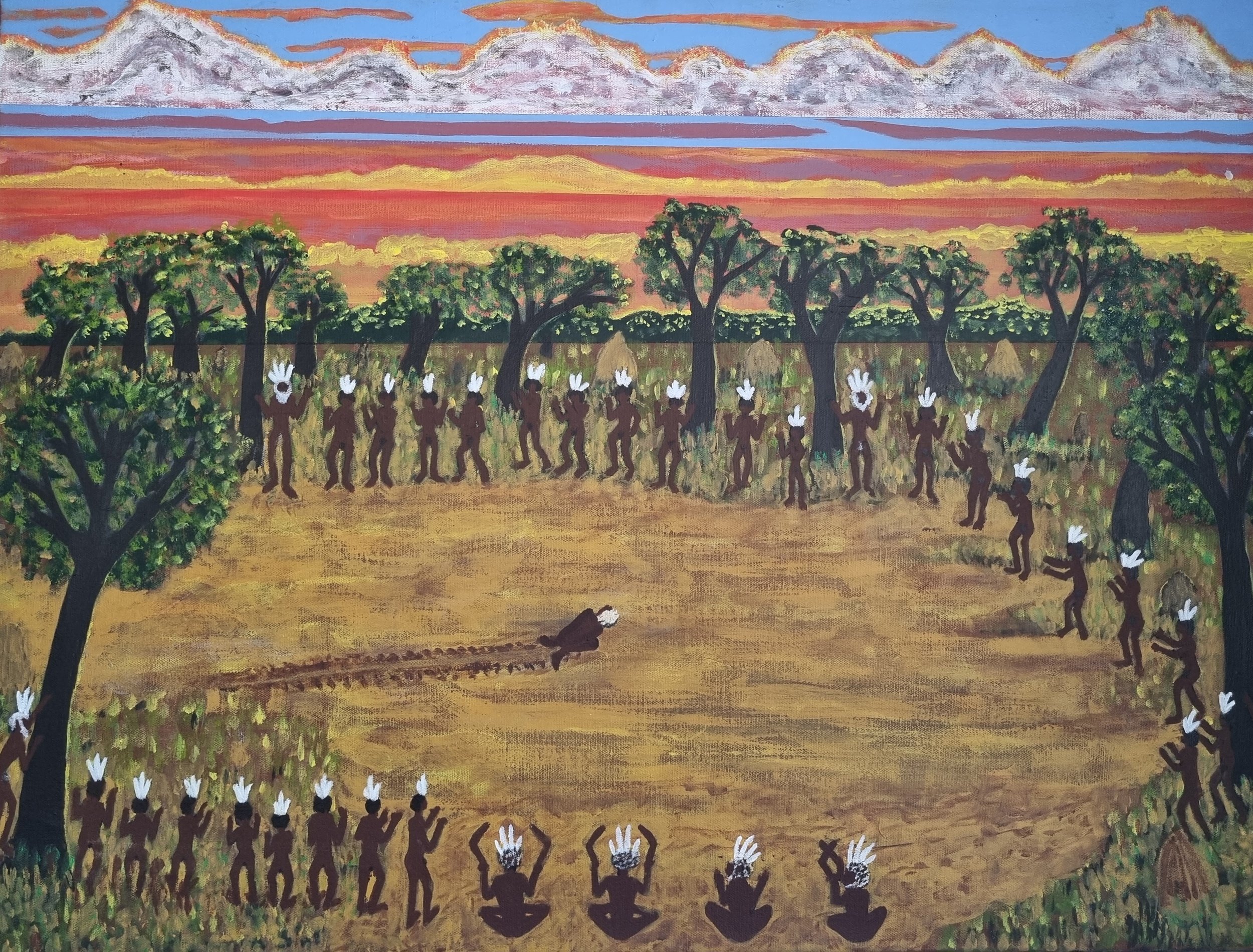

The late and great Granny Mavis Ngallametta (a cousin of my Grandmother, Jean Little OAM) led the charge. She—and at a similar time, Naomi Hobson—established a visual tradition depicting Country precisely, while also incorporating elements of purposeful “abstraction” to disguise the sacredness and hidden knowledge linked with a place. Over time, the more truly abstract and minimalist works of artists from the Lockhart River Art Gang came to the fore, as did the Hope Vale painters’ depictions of their township. What Granny Mavis and these other artists did—and what some are still doing—was to showcase their Country itself as well as their deep and inexplicable connections to their lands. Visual art is the medium through which these artists and Lorekeepers prove First Nations peoples’ place on and within Country, which is an important response to Wilderness Ideology’s attempt to divorce people from place.

Informed by a—perhaps subconscious—Wilderness Ideology, players in the art market still cater to the non-Indigenous thirst for First Nations artworks that maintain the image of an untouched, sunburnt land. Kowanyama artist Tania Major, a proud Kokoberra woman, has spoken to me in the past of the noticeable absence of Blak peoples in First Nations artists’ own works—especially those from remote and regional areas. In answer to this, Tania and her fellow Kowanyama artists have frequently shown portraits in many forms at the Cairns Indigenous Art Fair.

Tania herself is a decorated artist, having won the CIAF Innovation Art Award in 2022 for her painting Dragon Flys Everywhere: Coming Into The Dry Season (2022). Structurally, Tania’s dragonfly painting is innovative and offers a psychedelic view of Country, as though viewing the tangible and sustaining land through the spirit world. When looking at Tania’s work, the paintings of Uncle Syd Bruce Shortjoe (who is a proud Wik-Iiyanh man of the Wik Mynah people) from Pormpuraaw also spring to mind. To me, his works typify a unique school of landscape painting, which seems to only come from the Western Cape of Cape York Peninsula. There’s a multidimensional quality to his paintings and his works on paper: they appear as if you are looking simultaneously at, floating above and sitting within any given landscape. Granny Nita Yunkaporta from Aurukun (a Wik-Mungkan Elder) is another superb artist with a similar approach. In fact, this emerging school likely came from the women artists of Aurukun, including Granny Mavis Ngallametta.

The key factor in the landscape works of cousin Tania, Uncle Sid and Granny Nita is that they often feature their/our own peoples (or at least glimpses of them/us) living and working on the land—as do works by Wanda Gibson, Gertie Deeral, Daisy Hamlot and Dr Bernard Singleton. All these artists’ works are culturally authoritative and position First Nations people as part and parcel of Country, which is a riposte to Wilderness Ideology. The works of these great artists remind audiences of our eternal presence on our homelands, across our Country, while also celebrating the beauty and vibrancy of the bush.

Jack Wilkie-Jans (Teppathiggi/Tjungundji), Gimuy/Cairns

Jack Wilkie-Jans is a multi-disciplinary artist, arts worker, writer and an Aboriginal affairs advocate.