A revealing darkness: ‘Shadow Spirit’ at Flinders Street Station

/Rarely do I walk into an exhibition and find that I am instantly awed. Or, that I put my phone away and just experience the show. But in the case of Yorta Yorta curator Kimberley Moulton’s ‘Shadow Spirit’, I am, and I do.

‘Shadow Spirit’ is presented as part of the RISING festival in Naarm/Melbourne and is housed in the dilapidated top floor of Flinders Street Station. It is an immersive exhibition of 15 new commissions – a major selection being time-based art – by 30 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists who explore Ancestral knowledges and Indigenous epistemologies. Unknown and unseen to all but the First Peoples of so-called Australia, these Indigenous spirits of memories, and indeed spirits of Country, have been generously brought together by Moulton and the exhibiting artists to teach non-Indigenous audiences the multiple realms of Indigenous comprehension which cannot be defined.

As a Ngiyampaa person, it is not lost on me how, despite the settler-colonial power dynamics at play inside the old Federation-era building-cum-art space, Moulton has shaped the exhibition into a space of Indigeneity, rather than just for Indigeneity. For non-initiated non-Indigenous audiences, what I am speaking about is how Moulton’s curatorial decision to position artists of material, spiritual and intellectual Indigenous knowledges into clusters is a purposeful act to counter the settler-colonial architectural features of specific exhibition zones. Within this Indigenous sovereign display space, the arched windows and pressed tin (or otherwise moulded) ceiling panels lose their power. Artworks rise from darkness to embody that energy, where they encourage the unfolding of truths.

There is an implied route for audiences to take when they emerge from the lift. First is left, where the artworks are a little more in conversation with each other and where the rooms are more open and connected. It would be remiss of me not to mention the ambitious projection by Brian Robinson (Kala Lagaw Ya/Wuthathi) in this area, Zugubal: The Winds and Tides set the Pace. The work is in a room by itself and bleeds from the walls onto the floor and ceiling. It is an enveloping display that heavily draws on Robinson’s linocut prints, including the one shown in the opposite room, and gives particular emphasis to his technical skill as a printmaker. The animation sees Zugubal, or celestial beings, begin life and move through the space, dictating life on earth. They navigate and shape cultural practice under the watchful eye of Tagai, a star constellation which moves across the ceiling.

Nearby is Wiradjuri artist Karla Dickens’s Deeply Rooted, an incredibly moving comment on the destruction of Country, our trees, and an Indigenous ecology that has been connected to place since time immemorial. The upturned roots that form major parts of this series of works were sourced by Dickens following the destructive Lismore floods of 2022. Joining Dickens in this area is a sculpture by Vicki Couzens (Keerray Wooroong/Gunditjmara) and paintings by John Prince Siddon (Walmajarri), and tucked away in a separate room, watershadow, an installation of various media by Judy Watson (Waanyi). Combined, these are the few exceptions to the time-based artworks that unfold throughout the rest of the exhibition.

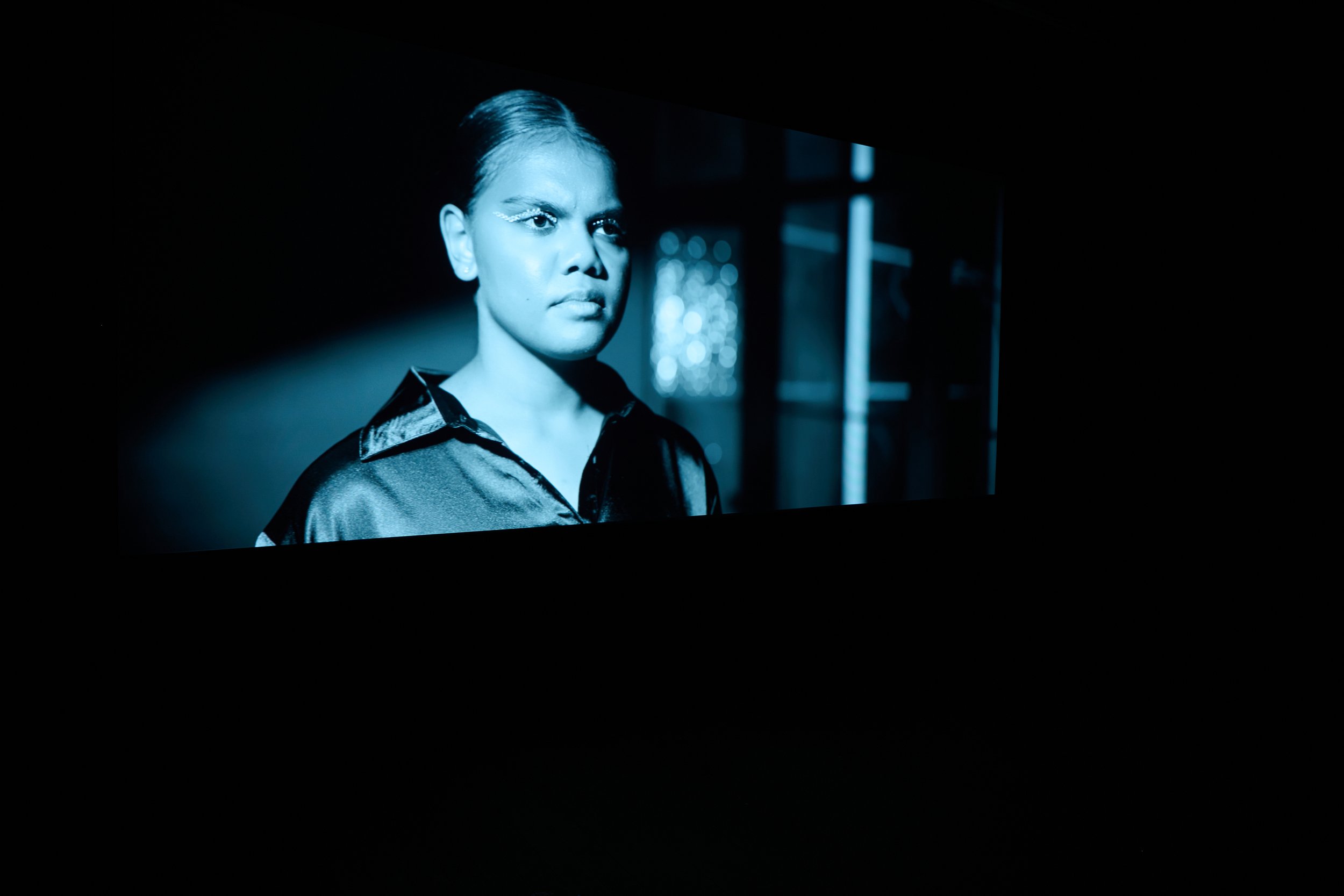

Within the right wing of the show, the first work viewers encounter is The Umbra by Hayley Millar Baker (Gunditjmara/Djabwurrung). The sound of heavy rain drew me into Millar Baker’s display, but it was the tender and slow pacing of the noir film that had me seated quickly. The film explores witching hour, when the veil between the spiritual and physical worlds is at its thinnest. There is a beautiful scene where The Umbra’s protagonist sits by the fireplace, mostly still, and in near silence. Opposite her is an empty armchair, but that is not really correct: an unknowing spirit sits alongside the protagonist, also warming herself by the fire. This is the second film from Millar Baker, following the success of her previous work Nyctinasty (2021), which continues to champion ideas of female magic and spirituality. As a young filmmaker, I am invested in seeing her practice continue and, with time, broaden.

While much of the exhibition releases haunting or sometimes distressing truths, there are elements of playfulness which reveal themselves through this section of the show. Moving along the hallway one encounters Way of the Ngangkari (2015) by Warwick Thornton (Kaytej), which likens the practice of ngangkari (healers) and their spiritual connections to Country to the school of force-wielding Jedis who originated in the movie franchise Star Wars. Nearby, Tiger Yaltangki (Pitjantjatjara) and Jeremy Whiskey (Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara) present ROCK N ROLL, an installation of Yaltangki’s painted guitars mounted as a framing device around the pair’s joint video work. Further down the corridor is a new animation by Dylan Mooney (Yuwi/Meriam and Australian South Sea Islander) that brings to life his digital drawings of plants, spirits and a young Aboriginal man. It is a welcome reprieve to encounter after the high-energy projection by Yaltangki and Whiskey. This is an astute decision on the part of Moulton, as curatorially she gives the viewer time to prepare for the introspection needed to encounter the final work in the ballroom.

Rarrirarri could arguably be considered the magnum opus of The Mulka Project with Mulkun Wirrpanda and of the exhibition itself. The work features a large termite mound sculpted from fibreglass in the centre of the room, with projections of Wirrpanda’s artworks that serve to document all the plants and insects from Yolngu Country, while exploring the cyclical nature of unseen ecologies. It is an exceptional installation, paired with a soundtrack of song and storytelling which reveals to an uninitiated and non-Indigenous audience that something spiritual and intellectual is happening. The work is both about sharing the unknowable and the championing of a Yolngu epistemology. It becomes a reflection on an Indigenous world of living where culture always comes first and where the unseen is sacred.

I believe ‘Shadow Spirit’ to be the most comprehensive showing of contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art that Naarm has seen in the last five years. It has so much to bring to light, with all the artists doing special and important work in speaking to the in-between and how this informs, shapes and changes the way Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people see the world. In such a divisive year of politics, non-Indigenous viewers can learn perspective through visiting the exhibition, to understand Indigenous knowledges and histories that they do not know or have not attempted yet to realise.

Erin Vink, Naarm/Melbourne

Curated by Kimberley Moulton and presented by Metro Trains Melbourne for this year’s RISING festival, ‘Shadow Spirit’ is being exhibited on Level 3 of Flinders Street Station until 30 July 2023.