Filling a cup in a river / working in the open: Lachlan Thompson in conversation with Stolon Press’s Tom Melick and Simryn Gill

/Started on Gadigal and Wangal land in 2019, Stolon Press was conceived by Tom Melick and Simryn Gill as: ‘a way to publish texts and images that might easily fall through cracks or remain in boxes and bottom drawers ... Like the plants from which it takes its name, Stolon Press works close to the ground, opportunistic in modest terrain and untended places.’ The following conversation took place over a period of two weeks or so this year. We initially arranged to meet in person, but ultimately decided that written correspondence would be best. The text has been passed back and forth, circulated, mulled over, written across weekends, during commutes and between deadlines.

Lachlan Thompson (LT): In thinking about publishing, I often find myself circling back to ideas around culture. When you write, make books, pamphlets and/or photocopies, is there a specific image/definition of culture that you have in mind?

Tom Melick (TM): Defining culture isn’t something we specifically think about when we’re making books, but you’re right to link the production of images and text (publishing) with the question of ‘culture’ more broadly. I’d say we try to get close to the word’s early usage, ‘to tend and cultivate’. Simryn likes to say we grow books, and I like that as an image and a method, because it implies an ecosystem. We work closely with the people we publish so the books come about through proximity, intimacy and persistence. An important aspect for us is that who we publish may not necessarily think of themselves as writers or artists, or perhaps do not even think what they do is publishable. But this isn’t charitable labour. We work with people we want to work with and want to read. So much of it is about what can come from conversation, and a book – even if it’s two pages stapled together, or one page folded in half – can be an excellent way to talk about something, to clarify, to organise, to combine, to compare, to record, to recover, to translate, to hold and then, eventually, to share. This places distribution – or a better word may be circulation? – at the very heart of publishing.

Since the 1990s, Arjun Appadurai has encouraged approaching culture not as a noun but as an adjective. As a noun, ‘culture is some kind of object, thing, or substance, whether physical or metaphysical’, whereas its adjectival use turns it into a heuristic device, ‘a dimension of phenomena, a dimension that attends to situated and embodied difference’. Publishers come in all shapes and sizes, and their motivations and aims are usually calibrated to certain authorships and readerships. Often, say in academic publishing today, those doing the writing and the reading are restricted by the professionalisation of language or by financial models, such as paywalls. The consequence of this is that academic discourse becomes less and less accessible; it partitions and divides between those who do research and writing and those who do not; those who study and those who are studied; those who operate within institutions and those who don’t. In other words, it loses its heuristics. Although we are still working this out, we want our books to travel and to find writers and readers who we couldn’t even imagine. Although the books we make are very simple, often photocopied and stapled, they are all carefully worked out in the making, and, ideally, they would travel like seeds, sprouting and growing in places we could never predict.

LT: Do you think there is a distinction constructed between conditions of production and content, and does a specific structure, type of content, aesthetics or poetics (maybe even politics) emerge from your publishing approach?

Simryn Gill (SG): The ‘content’ of what we do is held as much in the method of working – ‘conditions of production’ if you like – as in the address and subject matter of our publications. For us they’re impossible to separate.

Tom has described our approach to publishing. Think of it as a praxis. In our way of working, without planning to do this, praxis is a kind of reverse engineering – of theory; of ‘what is our politics’; of ‘how to be political’. We’re not so much putting some principles into practice, as figuring out our methodology through our activities. For us, being political in our time lies in thinking about how we live, thinking about what we do, the choices we make. Tom and I are drawn to working with people in an ecosystem (as our friend Khaled Sabsabi said of us) of friendships, connections and collaborations; tapping and sharing – pooling/pulling – skill, passion and our time. Inevitably this approach requires patience, flexibility, compromise, opportunism, slowness. We work slowly, at our pace and our authors’ and makers’ paces. We look for ways to fund our books, case by case, often choosing modesty as a solution to cost, but also because we learn a lot from putting the books together ourselves. As I’ve said, and it’s worth repeating: we learn from doing. Heuristics + Praxis. The books come out of this: are they by-products, manifestos, guidebooks? A way (for us) to live/make a living?

What I’m describing are high ideals. To work in the open, and openly, but still serious and generous to our authors and collaborators, our readers and ourselves. We often fall short, get frustrated, get things wrong; we are well aware that we are working from our own limitations (from our foibles, opinions, desires, egos). We also publish our own materials at Stolon Press. We make the frame, it also frames our own works – writings and images.

So what does this say about our ‘conditions of production’ and ‘content’? Messy and tangled, but also, we hope, clearly visible in their continuity and mutual dependence.

LT: I like the possible description of your books as by-products, something marginal, coming out of a larger or centralised process. Do you think that the book, as either an object or form, is capable of holding these conversations, friendships and ecosystems that grow/make them?

TM: A book can never hold the entirety of its process, or the conversations that go into its making. It’s a small part that you come away with, like filling a cup in a river. We often choose to work with people on multiple books, because it allows us to engage with different aspects of what they do over time, hopefully opening up new areas for them and for us. Form speaks directly to the experience of reading. We think a lot about the ‘objectness’ of a book (size, extent, paper, font, font size, margin size, cover and so on), but we’re not interested in fetishising print. Publishing can be an anxious business, and looking at the design of many books today this anxiousness creates a form that is both cautious and overdressed.

How do you trust a reader to find a book? To pick it up and be held by what’s inside? What books are capable of taking the full weight of our curiosity?

LT: At university, I remember being told that books can be thought of as a kind of architecture. Are there ways that you try to expand the ecosystems and structures that make up and surround books?

TM: I like the idea of thinking about a book’s conceptual and physical structure, and how the two can merge, so that the concept is experienced in the reading of the book rather than left as an abstraction. A book often brings with it a host of heterogeneous and contradictory parts, some of which are made visible through the process of making while others stay hidden ‘behind’ the face of the text like the cogs in a clock. There is no right way to go about it.

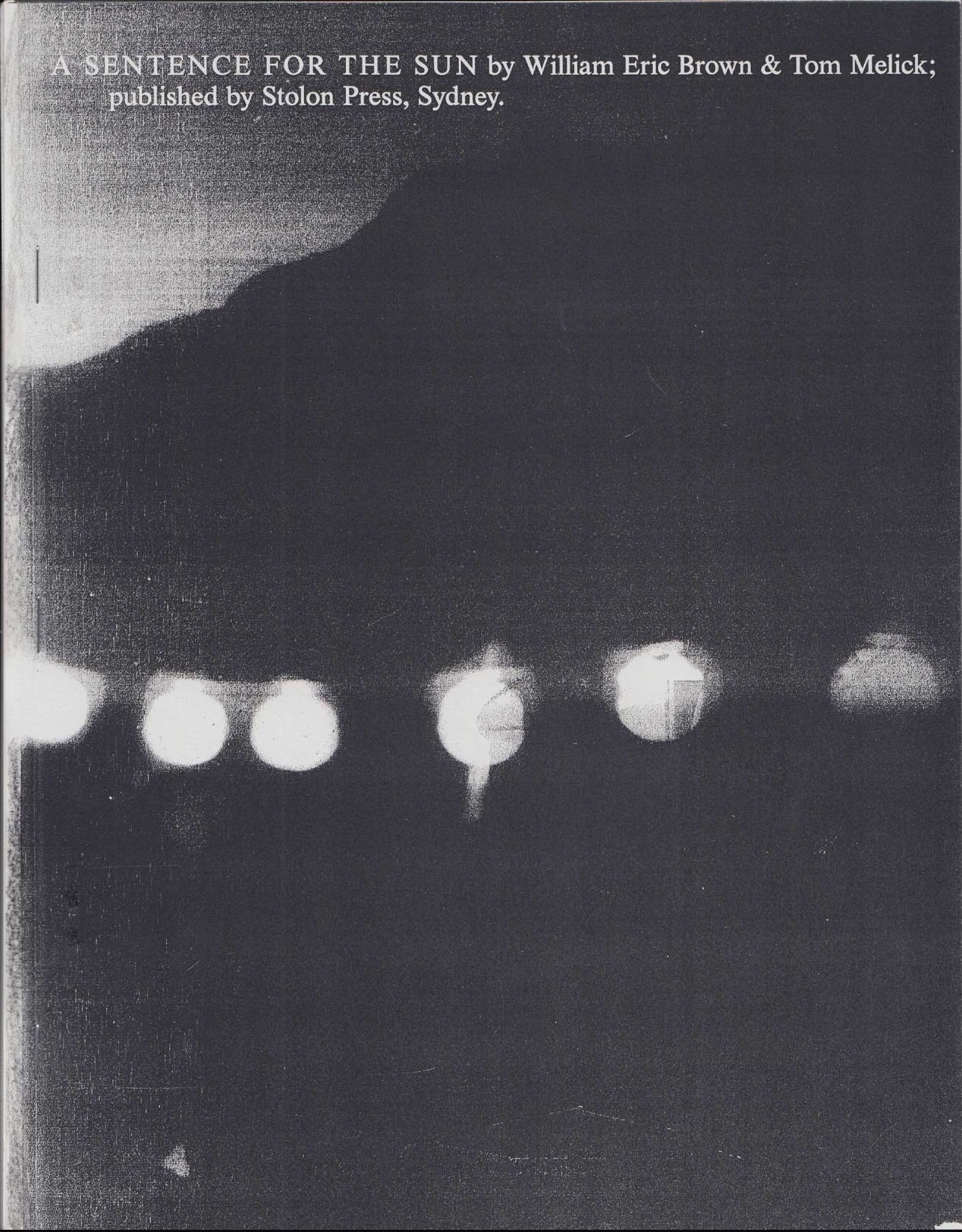

Simryn and I have chosen to place ourselves in the middle of these entanglements. We don’t have one method or process for bringing a book to print, common in trade and academic publishing. How can we translate a literal stolon collected from Botany Bay into a book (Coasting)? How can we combine text with images already painted and printed by an artist, such as William Eric Brown, into a story (A Sentence for the Sun, also 2022)? We approach the making of a book as a live event; we have to think on our feet and figure out how all the parts come together.

There are other models I admire, like the books my friend Elisa Taber shows me from her part of the world – from Cartonera Publishing. The books are bound together from recycled cardboard bought from cartoneros (‘garbage pickers’) and then handpainted. The books are sold at the cost of production, and they can be ‘ordered’ by readers like a pizza.

So perhaps we can think of books as different kinds of architecture? Some are houses, shelters, sheds, tents, skyscrapers, ruins. There are books with big wide hallways and others with narrow passages. Some books open interior spaces we’ve been in before, are familiar to us, while others surprise us.

Stolon Press’s most recent publications include Lee Weng Choy’s Hours, Accidental and Arbitrary: A Year of Writing Lonely, Aveek Sen’s Picture Book and Xenia Cherkaev’s St. Xenia and the Gleaners of Leningrad (all 2023); for more information, see Stolon Press.