Ecological variations, harmonic contemplation and songlines: ‘Hadley’s Art Prize 2022’

/‘Hadley’s Art Prize 2022’ celebrates the immense breadth of contemporary representations of the Australian landscape, bringing to the fore a multiplicity of voices that reflect on our cultural connection to the environment. Currently the most lucrative landscape award in Australia, it carries the same AU$100,000 prize money as the Archibald. Now in its fifth iteration, this year’s prize features 35 finalists selected from over 500 entrants, with the highest proportion of female finalists to date and the first female award recipient. Encompassing painting, photography and works on paper, the finalists broach the theme through an array of frameworks interrogating ideas such as connection to Country, secret or lost landscapes, the nature/culture nexus and environmental concerns.

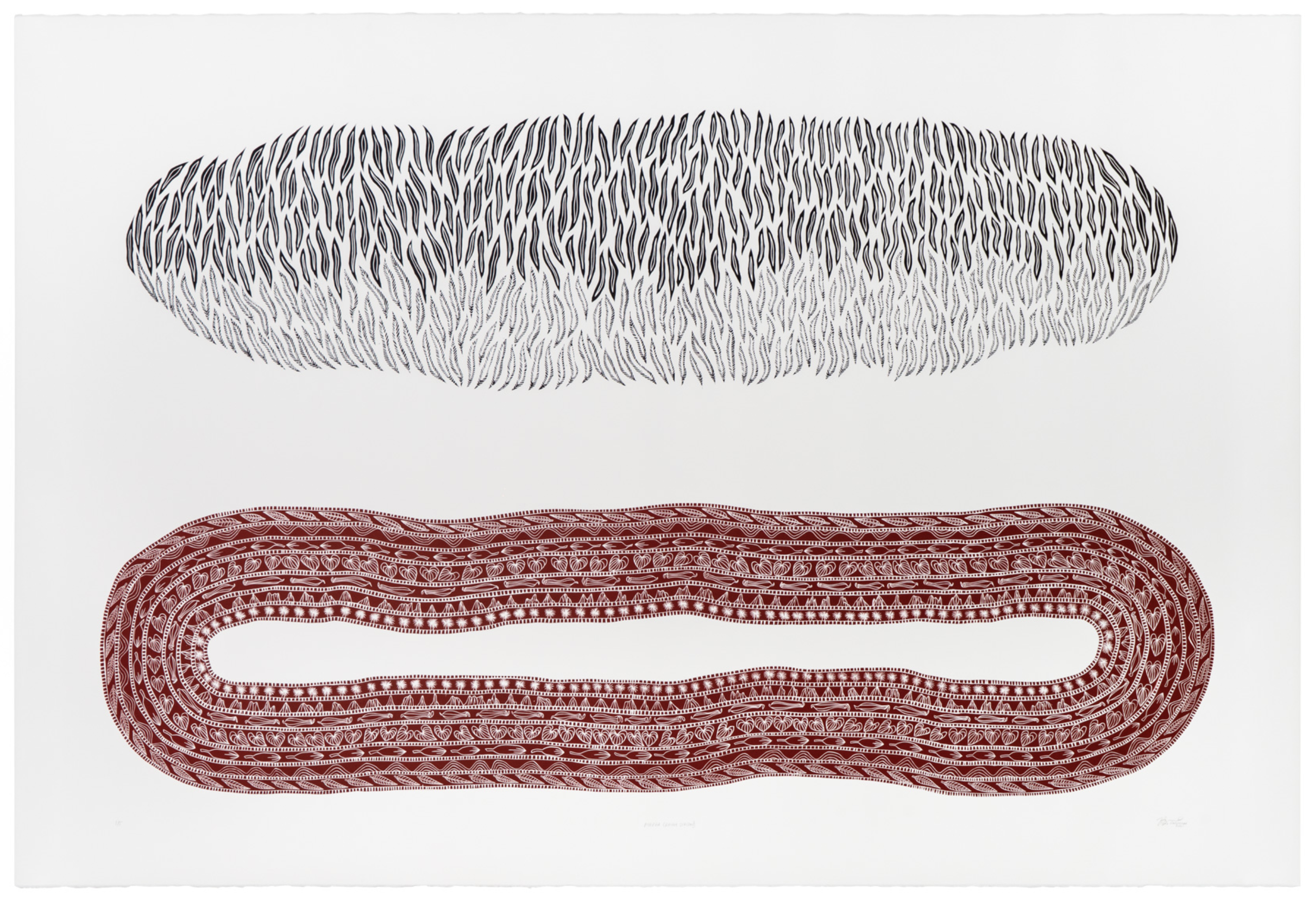

Senior Pitjantjatjara artist Tuppy Ngintja Goodwin from Mimili in the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands in South Australia won the 2022 prize with her painting Antara (2020). Her evocative work illustrates the Witchetty Grub (Maku) Tjukurpa from the Antara storyline, taught to her as a young girl. Goodwin depicts the three deep rock holes her community visits as part of this important ceremony. ‘This Tjukurpa holds so much for our women, for our people [and] is vital to the Maku life cycle and the continued prosperity,’ she told Art Monthly Australasia. Her intricate white dotting represents the Maku and is framed by a vibrant background that undulates with a cyclical energy. The broad sweeping brushstrokes in green, brown and yellow are symbolic of the verdant landscape and trees belonging to the Maku. Goodwin says she uses such bright hues in her artwork ‘because they are beautiful and powerful colours, just like this important Tjukurpa’. Goodwin’s expressive and layered palette echoes the vitality of the land, reflecting on the collective role of community as caretakers preserving the storylines of their Ancestors.

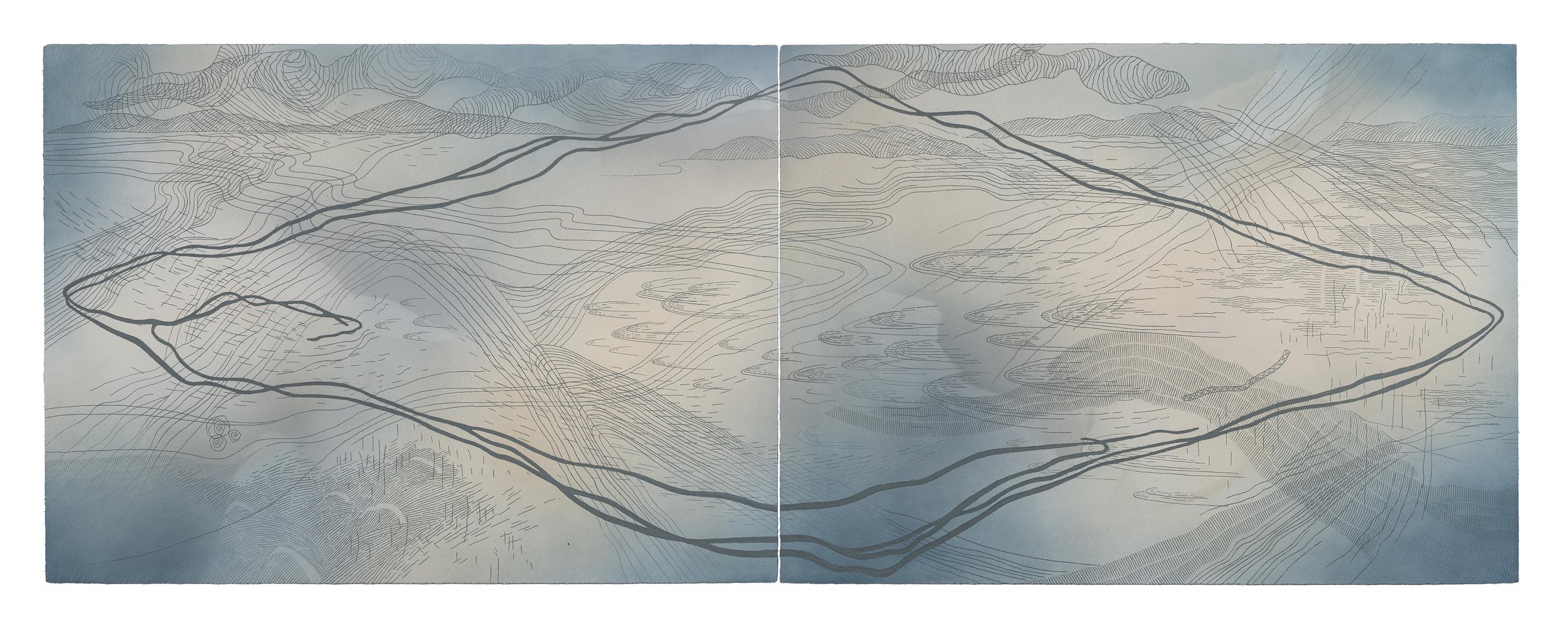

This year’s judges, Mary Knights, Wayne Tunnicliffe and Judy Watson (Waanyi), assessed the creativity, narrative and skill of the entries. Dexterity and expert command of technique can be witnessed in kanamaluka/Launceston artist Melissa Smith’s honourably mentioned intaglio collagraph print this hush – Lake Sorell (2022). Utilising both new and traditional printmaking processes, Smith poetically captures the passages of sound moving across this expansive body of water. Her delicate lines follow the patterns of gentle gusts of wind and swirling eddies as a quiet harmonic contemplation of the ever-changing environment.

Catherine Woo’s mixed-media painting on aluminium, A moment in the day (2022), speaks to light phenomena and transient moments. Awarded this year’s packing prize, her glimmering work evokes the scintillation of shifting light glinting against salt lakes or rippling water. Using the unconventional material of mica, Woo has built up delicate tonal layers of shimmering pigment reminiscent of iridescent nacre within a mollusc shell or oscillating light flickering between tree branches. It is in many ways a meditation on impermanence and the continual flux found within nature. The nipaluna/Hobart-based artist reflects on the cultural significance of this environmental wonder, which in Southeast Asia ‘is thought to embody a life force and creative energy, elusive and protean’ (according to her catalogue entry). Her evanescent painting is at once both a microcosmic and macrocosmic representation of the power of natural forces.

This year’s finalists include the early-career artists Harrison Bowe and Kate Lewis who both evocatively capture the sweeping wilderness experienced while bushwalking across lutruwita/Tasmania’s rugged terrain. Bowe lyrically depicts the sublime power of the Frankland Range in Beyond the Citadel. In Lewis’s Arduous Fantasy (also 2022), she reveals the vast ecological variation she witnessed hiking the Overland Track in 2021, traversing lush rainforests, alpine mountains and fields of vibrant button grass and pandanus trees. The physical act of immersion within the landscape occurs again in Bungambrawatha/Albury artist Nat Ward’s energetic painting Chocolate lily buds on Nail Can hill (2022), a vivid compilation of bush wattle, eucalyptus and chocolate lilies.

The works of art created by this year’s finalists show the expansive variety of individual and collective connections to Australia’s natural environment, with the winning work reminding us of a deeper caretaking that can take place through the poetic preservation of Ancestral storylines through the depicted landscape.

Rebecca Blake, nipaluna/Hobart

Curated by Amy Jackett, ‘Hadley’s Art Prize 2022’ is being exhibited at Hadley’s Orient Hotel, nipaluna/Hobart, until 21 August 2022.